Chapitre { }^{9:} Appercation

Chapitre 9 : { }^{9:} 9 : ¶ Définition: ¶ soit E, F deux ensembles.

On appelle application de E vers F tout “mode de association” qui à tout élément de E associe un unique élément de F.

Notation f : ∣ E ˉ → F x ↦ f ( x ) f: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \bar{E} \rightarrow F \\ & x \mapsto f(x)\end{aligned}\right. f : ∣ ∣ E ˉ → F x ↦ f ( x )

Vocabulaire: ¶ si b = f ( a ) b=f(a) b = f ( a )

Le graphe de f f f Γ = { ( x , y ) ∈ E × F ∣ y = f ( x ) } \Gamma=\{(x, y) \in E \times F \mid y=f(x)\} Γ = {( x , y ) ∈ E × F ∣ y = f ( x )} Γ = { ( x , f ( x ) ) ∣ x ∈ E } \Gamma=\{(x, f(x)) \mid x \in E\} Γ = {( x , f ( x )) ∣ x ∈ E }

L’ensemble E est appelé ensemble de départ (ou source).

L’ensemble F est appelé ensemble d’arrivée (ou but).

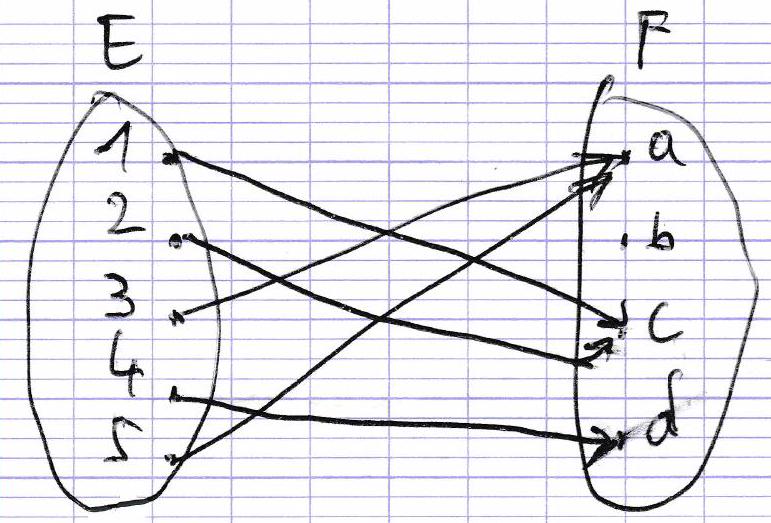

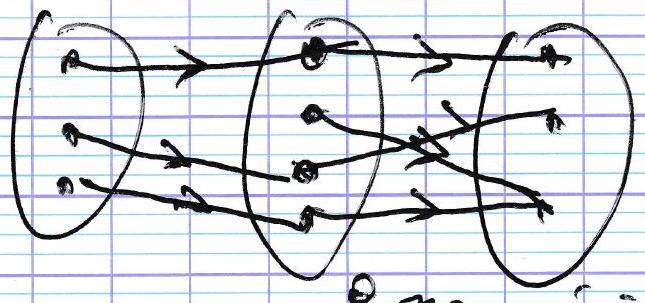

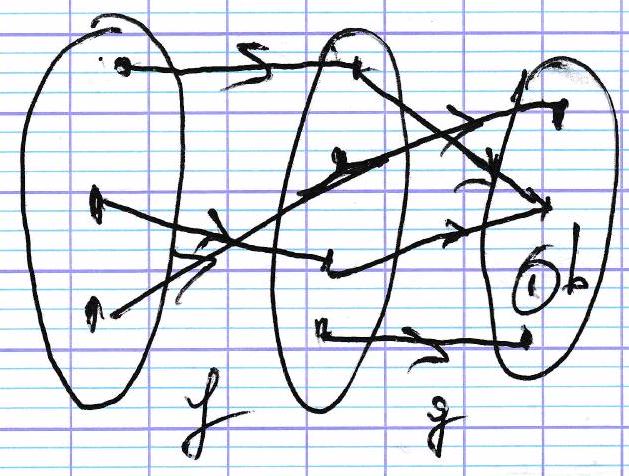

Représentation à l’aide d’un diagramme.

bon’ordre pas d’éléments parf c admet deux antécédents parf: Let 2 :

d admet exactement un antécédent parf: 4

Égalité de deux applications.

Soit f : ∣ E → F x ↦ f ( x ) f: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & E \rightarrow F \\ & x \mapsto f(x)\end{aligned}\right. f : ∣ ∣ E → F x ↦ f ( x ) g : ∣ G → H x ↦ g ( x ) g: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & G \rightarrow H \\ & x \mapsto g(x)\end{aligned}\right. g : ∣ ∣ G → H x ↦ g ( x ) f = g f=g f = g { E = b F = H ∀ x ∈ E , f ( x ) = g ( x ) \left\{\begin{array}{l}E=b \\ F=H \\ \forall x \in E, f(x)=g(x)\end{array}\right. ⎩ ⎨ ⎧ E = b F = H ∀ x ∈ E , f ( x ) = g ( x )

Application constante.

f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( ∀ y ∈ E ) ( f ( x ) = f ( y ) ) (\forall x \in E)(\forall y \in E)(f(x)=f(y)) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( ∀ y ∈ E ) ( f ( x ) = f ( y ))

Application indicatrice.

Soit E un ensemble et A un sous-ensemble de E.

L’application indicatrice est définie par!

I A ∣ E → { 0 , 1 } x ↦ { 0 , x ≠ 1 1 si x ≠ 1 \mathbb{I}_{A} \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned}

& E \rightarrow\{0,1\} \\

& x \mapsto\left\{\begin{array}{lll}

0, & x \neq 1 \\

1 & \text { si } & x \neq 1

\end{array}\right.

\end{aligned}\right. I A ∣ ∣ E → { 0 , 1 } x ↦ { 0 , 1 x = 1 si x = 1 Propriété: ¶ Soit A , B A, B A , B E E E

a) − 1 A ˉ = 1 − 1 A -\mathbb{1}_{\bar{A}}=1-\mathbb{1}_{A} − 1 A ˉ = 1 − 1 A − 1 A ∩ B = 1 A 1 B -\mathbb{1}_{A \cap B}=\mathbb{1}_{A} \mathbb{1}_{B} − 1 A ∩ B = 1 A 1 B − 1 A ∪ B = 1 A + 1 B − 1 A 1 B -\mathbb{1}_{A \cup B}=\mathbb{1}_{A}+\mathbb{1}_{B}-\mathbb{1}_{A} \mathbb{1}_{B} − 1 A ∪ B = 1 A + 1 B − 1 A 1 B

Preuve:

a) Soit x ∈ E x \in E x ∈ E

− si x ∈ A : 1 A ( x ) = 0 1 − 1 A ( x ) = 1 − 1 = 0 − si x ∉ A : 1 A ( x ) = 1 1 − 1 A ( x ) = 1 − 0 = 1 \begin{aligned}

& -\text{si } x \in A: \mathbb{1}_{A}(x)=0 \\

& 1-\mathbb{1}_{A}(x)=1-1=0 \\

& -\text{si } x \notin A: \mathbb{1}_{A}(x)=1 \\

& 1-\mathbb{1}_{A}(x)=1-0=1

\end{aligned} − si x ∈ A : 1 A ( x ) = 0 1 − 1 A ( x ) = 1 − 1 = 0 − si x ∈ / A : 1 A ( x ) = 1 1 − 1 A ( x ) = 1 − 0 = 1 ∀ x ∈ E , 1 A ( x ) = 1 − 1 A ( x ) \forall x \in E, \quad \mathbb{1}_{A}(x)=1-\mathbb{1}_{A}(x) ∀ x ∈ E , 1 A ( x ) = 1 − 1 A ( x ) b) Soit x ∈ E x \in E x ∈ E

− si x ∈ A ∩ B : 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 1 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) = 1 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 0 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) = 0 \begin{aligned}

&-\text{si } x \in A \cap B: \mathbb{1}_{A \cap B}(x)=1 \\

& \mathbb{1}_{A}(x) \mathbb{1}_{B}(x)=1 \\

& \mathbb{1}_{A \cap B}(x)=0 \\

& \mathbb{1}_{A}(x) \mathbb{1}_{B}(x)=0

\end{aligned} − si x ∈ A ∩ B : 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 1 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) = 1 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 0 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) = 0 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 0 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) = 0 \begin{aligned}

& \mathbb{1}_{A \cap B}(x)=0 \\

& \mathbb{1}_{A}(x) \mathbb{1}_{B}(x)=0

\end{aligned} 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 0 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) = 0 donc: ∀ x ∈ E , 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) \forall x \in E, \mathbb{1}_{A \cap B}(x)=\mathbb{1}_{A}(x) \mathbb{1}_{B}(x) ∀ x ∈ E , 1 A ∩ B ( x ) = 1 A ( x ) 1 B ( x ) A ∪ B ‾ = A ˉ ∩ B ˉ donc A ∪ B = A ˉ ∩ B ˉ \overline{A \cup B}=\bar{A} \cap \bar{B} \quad \text{donc} \quad A \cup B=\bar{A} \cap \bar{B} A ∪ B = A ˉ ∩ B ˉ donc A ∪ B = A ˉ ∩ B ˉ

1 A ∪ B = 1 − 1 A ˉ ∩ B ˉ = 1 − 1 A ˉ 1 B ˉ = 1 − ( 1 − 1 A ) ( 1 − 1 B ) = 1 A + 1 B − 1 A 1 B \begin{aligned}

\mathbb{1}_{A \cup B} & =1-\mathbb{1}_{\bar{A} \cap \bar{B}} \\

& =1-\mathbb{1}_{\bar{A}} \mathbb{1}_{\bar{B}} \\

& =1-\left(1-\mathbb{1}_{A}\right)\left(1-\mathbb{1}_{B}\right) \\

& =\mathbb{1}_{A}+\mathbb{1}_{B}-\mathbb{1}_{A} \mathbb{1}_{B}

\end{aligned} 1 A ∪ B = 1 − 1 A ˉ ∩ B ˉ = 1 − 1 A ˉ 1 B ˉ = 1 − ( 1 − 1 A ) ( 1 − 1 B ) = 1 A + 1 B − 1 A 1 B Révision, prolongement:

Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F A A A f f f f ∣ A f \mid A f ∣ A f ∣ A : ∣ A → F x ↦ f ( x ) f_{\mid A}: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & A \rightarrow F \\ & x \mapsto f(x)\end{aligned}\right. f ∣ A : ∣ ∣ A → F x ↦ f ( x ) x x x E E E g : x → F g: x \rightarrow F g : x → F f f f g g g g = f ∣ x g=f_{\mid x} g = f ∣ x

Exemple: ¶ exp: ∣ C → C z ↦ e z \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{C} \rightarrow \mathbb{C} \\ & z \mapsto e^{z}\end{aligned}\right. ∣ ∣ C → C z ↦ e z ∣ R → R x ↦ e x \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto e^{x}\end{aligned}\right. ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ e x

ψ ∣ C → R + z ↦ ∣ z ∣ \psi \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{C} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \\ & z \mapsto|z|\end{aligned}\right. ψ ∣ ∣ C → R + z ↦ ∣ z ∣ C \mathbb{C} C ∣ R → R + z ↦ ∣ z ∣ \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{+} \\ & z \mapsto|z|\end{aligned}\right. ∣ ∣ R → R + z ↦ ∣ z ∣

S ∣ z ↦ e i z + e − i z 2 C \left.S\right|_{z \mapsto \frac{e^{i z}+e^{-i z}}{2}} ^{\mathbb{C}} S ∣ z ↦ 2 e i z + e − i z C cos \cos cos ∣ R → R x ↦ cos ( x ) \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto \cos(x)\end{aligned}\right. ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ cos ( x )

Application induite:

Soit f : E → E f: E \rightarrow E f : E → E A A A E E E A A A f f f

si ∀ x ∈ A , f ( x ) ∈ A \text{si } \forall x \in A, f(x) \in A si ∀ x ∈ A , f ( x ) ∈ A Dans ce cas, l’application induite par f f f A A A

f ~ : ∣ A → A x ↦ f ( x ) \tilde{f}: \left\lvert\, \begin{array}{ll}

A & \rightarrow A \\

x & \mapsto f(x)

\end{array}\right. f ~ : ∣ ∣ A x → A ↦ f ( x ) Exemple:

f ( x ) = 2 + x f(x)=\sqrt{2+x} f ( x ) = 2 + x ] − 2 , + ∞ [ ]-2,+\infty[ ] − 2 , + ∞ [ R \mathbb{R} R x ∈ I = [ − 2 , + ∞ [ x \in I=[-2,+\infty[ x ∈ I = [ − 2 , + ∞ [

f ( x ) ⩾ 0 f(x) \geqslant 0 f ( x ) ⩾ 0 donc f ( x ) ∈ I = [ − 2 , + ∞ [ f(x) \in I=[-2,+\infty[ f ( x ) ∈ I = [ − 2 , + ∞ [

L’intervalle I est stable par f f f ( U n ) n ∈ N \left(U_{n}\right)_{n \in \mathbb{N}} ( U n ) n ∈ N { u 0 ∈ I ∀ n ∈ N , u n + 1 = f ( u n ) \left\{\begin{array}{l}u_{0} \in I \\ \forall n \in \mathbb{N}, u_{n+1}=f(u_{n})\end{array}\right. { u 0 ∈ I ∀ n ∈ N , u n + 1 = f ( u n )

Image directe, image réciproque.

Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F X X X E E E Y Y Y F F F

L’image directe de X X X f f f f ( X ) = { f ( x ) ∣ x ∈ X } = { y ∈ F ∣ ∃ x ∈ X , y = f ( x ) } f(X)=\{f(x) \mid x \in X\}=\{y \in F \mid \exists x \in X, y=f(x)\} f ( X ) = { f ( x ) ∣ x ∈ X } = { y ∈ F ∣ ∃ x ∈ X , y = f ( x )}

Exemples:

f : ∣ R → R x ↦ 0 f ( [ − 1 , 3 ] ) = { 0 } f ( R ) = { 0 } f: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto 0\end{aligned} \quad f([-1,3])=\{0\} \quad f(\mathbb{R})=\{0\}\right. f : ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ 0 f ([ − 1 , 3 ]) = { 0 } f ( R ) = { 0 }

f ( ∅ ) = ∅ f(\emptyset)=\emptyset f ( ∅ ) = ∅ f : ∣ R → R x ↦ x 2 − 4 x + 3 f: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto x^{2}-4 x+3\end{aligned}\right. f : ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ x 2 − 4 x + 3

a) f ( R ) = [ − 1 , + ∞ [ f(\mathbb{R})=[-1,+\infty[ f ( R ) = [ − 1 , + ∞ [

b) f ( [ 0 , 5 ] ) = [ − 1 , 8 ] c) f ( [ − 3 , 1 ] ) = [ 0 , 24 ] \begin{aligned}

& \text{b) } f([0,5])=[-1,8] \\

& \text{c) } f([-3,1])=[0,24]

\end{aligned} b) f ([ 0 , 5 ]) = [ − 1 , 8 ] c) f ([ − 3 , 1 ]) = [ 0 , 24 ] a) Soit x ∈ R x \in \mathbb{R} x ∈ R

f ( x ) + 4 = x 2 − 4 x + 4 = ( x − 2 ) 2 ⩾ 0 f(x)+4=x^{2}-4 x+4=(x-2)^{2} \geqslant 0 f ( x ) + 4 = x 2 − 4 x + 4 = ( x − 2 ) 2 ⩾ 0 Pour tout x ∈ R , f ( x ) ∈ [ − 1 , + ∞ [ x \in \mathbb{R}, f(x) \in[-1,+\infty[ x ∈ R , f ( x ) ∈ [ − 1 , + ∞ [ f ( R ) ⊂ [ − 1 , + ∞ [ f(\mathbb{R}) \subset [-1,+\infty[ f ( R ) ⊂ [ − 1 , + ∞ [

Soit y ∈ [ − 1 , + ∞ [ y \in[-1,+\infty[ y ∈ [ − 1 , + ∞ [ y + 1 ⩾ 0 y+1 \geqslant 0 y + 1 ⩾ 0 ⇒ y + 1 = ( y + 1 ) 2 = ( y + 1 + 2 − 2 ) 2 \Rightarrow y+1=(\sqrt{y+1})^{2}=(\sqrt{y+1}+2-2)^{2} ⇒ y + 1 = ( y + 1 ) 2 = ( y + 1 + 2 − 2 ) 2 x = y + 1 + 2 x=\sqrt{y+1}+2 x = y + 1 + 2 f ( x ) = − 1 + ( x − 2 ) 2 = y f(x)=-1+(x-2)^{2}=y f ( x ) = − 1 + ( x − 2 ) 2 = y y ∈ f ( R ) y \in f(\mathbb{R}) y ∈ f ( R ) [ − 1 , + ∞ [ ⊂ f ( R ) [-1,+\infty[ \subset f(\mathbb{R}) [ − 1 , + ∞ [ ⊂ f ( R ) f ( R ) = [ − 1 , + ∞ [ f(\mathbb{R})=[-1,+\infty[ f ( R ) = [ − 1 , + ∞ [

b) Soit x ∈ [ 0 , 5 ] x \in[0,5] x ∈ [ 0 , 5 ] − 2 ≤ x − 2 ≤ 3 -2 \leq x-2 \leq 3 − 2 ≤ x − 2 ≤ 3 0 ≤ ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 9 0 \leq(x-2)^{2} \leq 9 0 ≤ ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 9

− 1 ≤ − 1 + ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 8 − 1 ≤ f ( x ) ≤ 8 \begin{gathered}

-1 \leq-1+(x-2)^{2} \leq 8 \\

-1 \leq f(x) \leq 8

\end{gathered} − 1 ≤ − 1 + ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 8 − 1 ≤ f ( x ) ≤ 8 donc f ( x ) ∈ [ − 1 , 8 ] f(x) \in[-1,8] f ( x ) ∈ [ − 1 , 8 ] f ( [ 0 , 5 ] ) ⊂ [ − 1 , 8 ] f([0,5]) \subset[-1,8] f ([ 0 , 5 ]) ⊂ [ − 1 , 8 ]

Réciproquement, soit y ∈ [ − 1 , 8 ] y \in[-1,8] y ∈ [ − 1 , 8 ]

y = − 1 + ( 2 + y + 1 x 2 − 2 ) 2 = − 1 + ( x − 2 ) 2 = f ( x ) \begin{aligned}

y & =-1+\left(\frac{2+\sqrt{y+1}}{x^{2}}-2\right)^{2} \\

& =-1+(x-2)^{2} \\

& =f(x)

\end{aligned} y = − 1 + ( x 2 2 + y + 1 − 2 ) 2 = − 1 + ( x − 2 ) 2 = f ( x ) or x = 2 + y + 1 x=2+\sqrt{y+1} x = 2 + y + 1 0 ≤ y ⩽ 9 0 \leq y \leqslant 9 0 ≤ y ⩽ 9 0 ≤ y + 1 ⩽ 3 0 \leq \sqrt{y+1} \leqslant 3 0 ≤ y + 1 ⩽ 3 2 ≤ x ⩽ 5 2 \leq x \leqslant 5 2 ≤ x ⩽ 5 y ∈ f ( [ 0 , 5 ] ) y \in f([0,5]) y ∈ f ([ 0 , 5 ])

c) f f f [ − 3 , 1 ] [-3,1] [ − 3 , 1 ] [ − 3 , 1 ] [-3,1] [ − 3 , 1 ] [ f ( 1 ) , f ( − 3 ) ] = [ 0 , 24 ] [f(1), f(-3)] = [0,24] [ f ( 1 ) , f ( − 3 )] = [ 0 , 24 ]

Ainsi: f ( [ − 3 , 1 ] ) = [ 0 , 24 ] f([-3,1])=[0,24] f ([ − 3 , 1 ]) = [ 0 , 24 ]

f : C ∗ → C f: \mathbb{C}^{*} \rightarrow \mathbb{C} f : C ∗ → C

z ↦ z + 1 z U = { z ∈ C ∣ ∣ z ∣ = 1 } f ( U ) ? \begin{aligned}

z \mapsto z+\frac{1}{z} \\

U=\{z \in \mathbb{C} \mid |z|=1\} \quad f(U) ?

\end{aligned} z ↦ z + z 1 U = { z ∈ C ∣ ∣ z ∣ = 1 } f ( U )? Montrons que f ( U ) = [ − 2 , 2 ] f(U)=[-2,2] f ( U ) = [ − 2 , 2 ]

f ( z ) = z + 1 z = z + z ˉ = 2 Re ( z ) \begin{aligned}

f(z) & =z+\frac{1}{z} \\

& =z+\bar{z} \\

& =2 \operatorname{Re}(z)

\end{aligned} f ( z ) = z + z 1 = z + z ˉ = 2 Re ( z ) Or pour tout z ∈ C z \in \mathbb{C} z ∈ C Re ( z ) ⩽ ∣ z ∣ \operatorname{Re}(z) \leqslant |z| Re ( z ) ⩽ ∣ z ∣ 2 Re ( z ) ⩽ 2 2 \operatorname{Re}(z) \leqslant 2 2 Re ( z ) ⩽ 2 f ( z ) ∈ [ − 2 , 2 ] f(z) \in[-2,2] f ( z ) ∈ [ − 2 , 2 ] f ( U ) ⊂ [ − 2 , 2 ] f(U) \subset[-2,2] f ( U ) ⊂ [ − 2 , 2 ]

Réciproquement, soit y ∈ [ − 2 , 2 ] y \in[-2,2] y ∈ [ − 2 , 2 ] ¶ Il existe θ ∈ R \theta \in \mathbb{R} θ ∈ R y = 2 cos ( θ ) y=2 \cos(\theta) y = 2 cos ( θ ) z = e i θ ∈ U z=e^{i \theta} \in \mathbb{U} z = e i θ ∈ U

y = e i θ + 1 e i θ y = f ( e i θ ) \begin{aligned}

& y=e^{i \theta}+\frac{1}{e^{i \theta}} \\

& y=f\left(e^{i \theta}\right)

\end{aligned} y = e i θ + e i θ 1 y = f ( e i θ ) et e i θ ∈ U e^{i \theta} \in \mathbb{U} e i θ ∈ U [ − 2 , 2 ] ⊂ f ( U ) [-2,2] \subset f(\mathbb{U}) [ − 2 , 2 ] ⊂ f ( U )

Exemples:

f : ∣ R → R x ↦ x 2 − 4 x + 3 f: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto x^{2}-4 x+3\end{aligned}\right. f : ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ x 2 − 4 x + 3

a) f − 1 ( [ − 4 , 1 ] ) = { 2 } b) f − 1 ( [ 0 , 3 ] ) x ∈ f − 1 ( [ 0 , 3 ] ) ⇔ f ( x ) ∈ [ 0 , 3 ] ⇔ 0 ≤ f ( x ) ≤ 3 ⇔ 1 ≤ ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 4 ⇔ 1 ≤ x − 2 < 2 ou − 2 ≤ x − 2 ≤ − 1 ⇔ 3 ≤ x ≤ 4 ou 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 f − 1 ( [ 0 , 3 ] ) = [ 0 , 1 ] ∪ [ 3 , 4 ] \begin{aligned}

& \text{a) } f^{-1}([-4,1])=\{2\} \\

& \text{b) } f^{-1}([0,3]) \\

& x \in f^{-1}([0,3]) \Leftrightarrow f(x) \in[0,3] \\

& \Leftrightarrow 0 \leq f(x) \leq 3 \Leftrightarrow 1 \leq(x-2)^{2} \leq 4 \\

& \Leftrightarrow 1 \leq x-2 < 2 \text{ ou } -2 \leq x-2 \leq-1 \\

& \Leftrightarrow 3 \leq x \leq 4 \text{ ou } 0 \leq x \leq 1 \\

& f^{-1}([0,3])=[0,1] \cup[3,4]

\end{aligned} a) f − 1 ([ − 4 , 1 ]) = { 2 } b) f − 1 ([ 0 , 3 ]) x ∈ f − 1 ([ 0 , 3 ]) ⇔ f ( x ) ∈ [ 0 , 3 ] ⇔ 0 ≤ f ( x ) ≤ 3 ⇔ 1 ≤ ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 4 ⇔ 1 ≤ x − 2 < 2 ou − 2 ≤ x − 2 ≤ − 1 ⇔ 3 ≤ x ≤ 4 ou 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 f − 1 ([ 0 , 3 ]) = [ 0 , 1 ] ∪ [ 3 , 4 ] c) x ∈ f − 1 ( [ − 1 ; 8 ] ) ⇔ 1 ⩽ f ( x ) ≤ 8 x \in f^{-1}([-1 ; 8]) \Leftrightarrow 1 \leqslant f(x) \leq 8 x ∈ f − 1 ([ − 1 ; 8 ]) ⇔ 1 ⩽ f ( x ) ≤ 8

⇔ 2 ≤ ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 9 ⇔ 2 ≤ x − 2 ≤ 3 ou − 3 ≤ x − 2 ≤ − 2 ⇔ 2 + 2 ≤ x ≤ 5 ou 2 − 2 ≤ x ≤ 2 − 2 f − 1 ( [ − 1 , 8 ] ) = [ − 1 , 2 − 2 ] ∪ [ 2 + 2 , 5 ] \begin{aligned}

& \Leftrightarrow 2 \leq(x-2)^{2} \leq 9 \\

& \Leftrightarrow \sqrt{2} \leq x-2 \leq 3 \\

& \text{ ou } -3 \leq x-2 \leq-\sqrt{2} \\

& \Leftrightarrow 2+\sqrt{2} \leq x \leq 5 \text{ ou } 2-\sqrt{2} \leq x \leq 2-\sqrt{2} \\

f^{-1}([-1,8])= & {[-1,2-\sqrt{2}] \cup[2+\sqrt{2}, 5] }

\end{aligned} f − 1 ([ − 1 , 8 ]) = ⇔ 2 ≤ ( x − 2 ) 2 ≤ 9 ⇔ 2 ≤ x − 2 ≤ 3 ou − 3 ≤ x − 2 ≤ − 2 ⇔ 2 + 2 ≤ x ≤ 5 ou 2 − 2 ≤ x ≤ 2 − 2 [ − 1 , 2 − 2 ] ∪ [ 2 + 2 , 5 ] Soit f : C − { − i } → C f: \mathbb{C}-\{-i\} \rightarrow \mathbb{C} f : C − { − i } → C

z ↦ z − i z + i a) f − 1 ( R ) b) f − 1 ( R i ) \begin{array}{ll}

z \mapsto \frac{z-i}{z+i} & \text{a) } f^{-1}(\mathbb{R}) \\

& \text{b) } f^{-1}(\mathbb{R} i)

\end{array} z ↦ z + i z − i a) f − 1 ( R ) b) f − 1 ( R i ) a) z ∈ f − 1 ( R ) ⇔ f ( z ) ∈ R z \in f^{-1}(\mathbb{R}) \Leftrightarrow f(z) \in \mathbb{R} z ∈ f − 1 ( R ) ⇔ f ( z ) ∈ R

⇔ z − i z + i = z ˉ + i z ˉ − i ⇔ ∣ z ∣ 2 − i z + i z ˉ − 1 = ∣ z ∣ 2 + i z + i z ˉ − 1 ⇔ i z + i z ˉ = 0 ⇔ z + z ˉ = 0 f − 1 ( R ) = R i − { − i } \begin{aligned}

& \Leftrightarrow \frac{z-i}{z+i}=\frac{\bar{z}+i}{\bar{z}-i} \\

& \Leftrightarrow \left|z\right|^{2}-i z+i \bar{z}-1=|z|^{2}+i z+i \bar{z}-1 \\

& \Leftrightarrow i z+i \bar{z}=0 \\

& \Leftrightarrow z+\bar{z}=0 \\

& f^{-1}(\mathbb{R})=\mathbb{R} i-\{-i\}

\end{aligned} ⇔ z + i z − i = z ˉ − i z ˉ + i ⇔ ∣ z ∣ 2 − i z + i z ˉ − 1 = ∣ z ∣ 2 + i z + i z ˉ − 1 ⇔ i z + i z ˉ = 0 ⇔ z + z ˉ = 0 f − 1 ( R ) = R i − { − i } b) z ∈ f − 1 ( R i ) ⇔ f ( z ) ∈ R i z \in f^{-1}(\mathbb{R} i) \Leftrightarrow f(z) \in \mathbb{R} i z ∈ f − 1 ( R i ) ⇔ f ( z ) ∈ R i

⇔ z − i z + i = − z ˉ − i z ˉ − i ⇔ ∣ z ∣ 2 − i z + i z − 1 = − ( ∣ z ∣ 2 + i z + i z ˉ − 1 ) ⇔ 2 ∣ z ∣ 2 − 2 = 0 ⇔ ∣ z ∣ ≥ 1 \begin{aligned}

& \Leftrightarrow \frac{z-i}{z+i}=\frac{-\bar{z}-i}{\bar{z}}-i \\

& \Leftrightarrow|z|^{2}-i z+i z-1=-\left(|z|^{2}+i z+i \bar{z}-1\right) \\

& \Leftrightarrow 2|z|^{2}-2=0 \\

& \Leftrightarrow|z| \geq 1

\end{aligned} ⇔ z + i z − i = z ˉ − z ˉ − i − i ⇔ ∣ z ∣ 2 − i z + i z − 1 = − ( ∣ z ∣ 2 + i z + i z ˉ − 1 ) ⇔ 2∣ z ∣ 2 − 2 = 0 ⇔ ∣ z ∣ ≥ 1 f − 1 ( R i ) = C − { − i } f^{-1}(\mathbb{R} i)=\mathbb{C}-\{-i\} f − 1 ( R i ) = C − { − i }

Famille:

Soit I un ensemble non vide et E un ensemble. On appelle famille de E E E I → E i ↦ x \begin{aligned} I & \rightarrow E \\ i & \mapsto x\end{aligned} I i → E ↦ x

I: ensemble d’indices appelés indices. On la note ( x i ) i ∈ I \left(x_{i}\right)_{i \in I} ( x i ) i ∈ I

Dans le cas où I = N I=\mathbb{N} I = N E E E

Exemples: ¶ Pour tout α ∈ R \alpha \in \mathbb{R} α ∈ R f α : R → R f_{\alpha}: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} f α : R → R x ↦ e α x x \mapsto e^{\alpha x} x ↦ e αx

On dispose là d’une famille de fonctions indexée par R \mathbb{R} R

Pour tout r > 0 r > 0 r > 0 J r = ] − r , r [ J_r = \left]-r, r\right[ J r = ] − r , r [ ( J n ) \left(J_n\right) ( J n )

Généralisation de V , N V, N V , N

Soit ( A i ) i ∈ I \left(A_i\right)_{i \in I} ( A i ) i ∈ I E E E

⋃ i ∈ I A i = { x ∈ E ∣ ∃ i ∈ I , x ∈ A i } ⋂ i ∈ I A i = { x ∈ E ∣ ∀ i ∈ I , x ∈ A i } \begin{aligned}

& \bigcup_{i \in I} A_i = \left\{ x \in E \mid \exists i \in I, x \in A_i \right\} \\

& \bigcap_{i \in I} A_i = \left\{ x \in E \mid \forall i \in I, x \in A_i \right\}

\end{aligned} i ∈ I ⋃ A i = { x ∈ E ∣ ∃ i ∈ I , x ∈ A i } i ∈ I ⋂ A i = { x ∈ E ∣ ∀ i ∈ I , x ∈ A i } Lois de De Morgan :

⋃ i ∈ I A i ‾ = ⋂ i ∈ I A i ‾ ⋂ i ∈ I A i ‾ = ⋃ i ∈ I A i ‾ \begin{aligned}

& \overline{\bigcup_{i \in I} A_i} = \bigcap_{i \in I} \overline{A_i} \\

& \overline{\bigcap_{i \in I} A_i} = \bigcup_{i \in I} \overline{A_i}

\end{aligned} i ∈ I ⋃ A i = i ∈ I ⋂ A i i ∈ I ⋂ A i = i ∈ I ⋃ A i Partition d’un ensemble :

Soit E E E { A i ∣ i ∈ I } \left\{ A_i \mid i \in I \right\} { A i ∣ i ∈ I } E E E

Les sous-ensembles A i A_i A i i ∈ I i \in I i ∈ I E E E

∀ i ∈ I , A i ≠ ∅ \forall i \in I, A_i \neq \varnothing ∀ i ∈ I , A i = ∅

( ∀ i ∈ I ) ( ∀ j ∈ I ) ( i ≠ j ⇒ A i ∩ A j = ∅ ) (\forall i \in I)(\forall j \in I) \left( i \neq j \Rightarrow A_i \cap A_j = \varnothing \right) ( ∀ i ∈ I ) ( ∀ j ∈ I ) ( i = j ⇒ A i ∩ A j = ∅ )

E = ⋃ i ∈ I A i E = \bigcup_{i \in I} A_i E = ⋃ i ∈ I A i

Exemples : ¶ Z 2 \mathbb{Z}_2 Z 2 2 i 2i 2 i { Z 0 , Z 1 } \left\{ \mathbb{Z}_0, \mathbb{Z}_1 \right\} { Z 0 , Z 1 } E E E

Soit N ∈ N ∗ − { 1 } N \in \mathbb{N}^* - \{1\} N ∈ N ∗ − { 1 }

Z k = { n ∈ Z ∣ n ≡ k ( m o d N ) } k ∈ Z k donc Z k ≠ ∅ \begin{aligned}

& \mathbb{Z}_k = \left\{ n \in \mathbb{Z} \mid n \equiv k \pmod{N} \right\} \\

& k \in \mathbb{Z}_k \text{ donc } \mathbb{Z}_k \neq \varnothing

\end{aligned} Z k = { n ∈ Z ∣ n ≡ k ( mod N ) } k ∈ Z k donc Z k = ∅ Z 0 , Z 1 , … , Z N − 1 \mathbb{Z}_0, \mathbb{Z}_1, \ldots, \mathbb{Z}_{N-1} Z 0 , Z 1 , … , Z N − 1 Z \mathbb{Z} Z

Soient p , q p, q p , q 0 ⩽ p ⩽ q ⩽ N − 1 0 \leqslant p \leqslant q \leqslant N-1 0 ⩽ p ⩽ q ⩽ N − 1

Supposons Z p ∩ Z q ≠ ∅ \mathbb{Z}_p \cap \mathbb{Z}_q \neq \varnothing Z p ∩ Z q = ∅

Soit x ∈ Z p ∩ Z q x \in \mathbb{Z}_p \cap \mathbb{Z}_q x ∈ Z p ∩ Z q

x ≡ p ( m o d N ) x \equiv p \pmod{N} x ≡ p ( mod N )

et x ≡ q ( m o d N ) x \equiv q \pmod{N} x ≡ q ( mod N )

donc p ≡ q ( m o d N ) p \equiv q \pmod{N} p ≡ q ( mod N )

donc q − p q - p q − p N N N

Or 0 ⩽ q − p ⩽ N − 1 0 \leqslant q - p \leqslant N - 1 0 ⩽ q − p ⩽ N − 1 q − p = 0 q - p = 0 q − p = 0

Par contraposée, si p ≠ q p \neq q p = q Z p ∩ Z q = ∅ \mathbb{Z}_p \cap \mathbb{Z}_q = \varnothing Z p ∩ Z q = ∅

∀ k ∈ ⟦ 0 , N − 1 ⟧ , Z k ⊂ Z \forall k \in \llbracket 0, N-1 \rrbracket, \mathbb{Z}_k \subset \mathbb{Z} ∀ k ∈ [ [ 0 , N − 1 ] ] , Z k ⊂ Z ⋃ k = 0 N − 1 Z k ⊂ Z \bigcup_{k=0}^{N-1} \mathbb{Z}_k \subset \mathbb{Z} ⋃ k = 0 N − 1 Z k ⊂ Z

Réciproquement, soit x ∈ Z x \in \mathbb{Z} x ∈ Z

Par division euclidienne de x x x N N N q ∈ Z q \in \mathbb{Z} q ∈ Z r ∈ ⟦ 0 , N − 1 ⟧ r \in \llbracket 0, N-1 \rrbracket r ∈ [ [ 0 , N − 1 ] ] x = N q + r x = Nq + r x = Nq + r

donc x ∈ Z r x \in \mathbb{Z}_r x ∈ Z r

Ce qui montre que Z ⊂ ⋃ k = 0 N − 1 Z k \mathbb{Z} \subset \bigcup_{k=0}^{N-1} \mathbb{Z}_k Z ⊂ ⋃ k = 0 N − 1 Z k

Par double inclusion :

Z = ⋃ k = 0 N − 1 Z k \mathbb{Z} = \bigcup_{k=0}^{N-1} \mathbb{Z}_k Z = ⋃ k = 0 N − 1 Z k

Z k \mathbb{Z}_k Z k k k k N N N

Q , R − Q \mathbb{Q}, \mathbb{R} - \mathbb{Q} Q , R − Q R \mathbb{R} R

Application injective, surjective, bijective

Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F

On s’intéresse à l’équation f ( x ) = b f(x) = b f ( x ) = b b ∈ F b \in F b ∈ F

On note N ( b ) N(b) N ( b ) f ( x ) = b f(x) = b f ( x ) = b

On dit que f f f

C’est-à-dire tout élément b ∈ F b \in F b ∈ F E E E f f f

Si : ∀ b ∈ F , N ( b ) ⩾ 1 \forall b \in F, N(b) \geqslant 1 ∀ b ∈ F , N ( b ) ⩾ 1 b ∈ F b \in F b ∈ F E E E f f f

Définition : Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F

On dit que f f f E E E F F F ∀ y ∈ F , ∃ x ∈ E , y = f ( x ) \forall y \in F, \exists x \in E, y = f(x) ∀ y ∈ F , ∃ x ∈ E , y = f ( x )

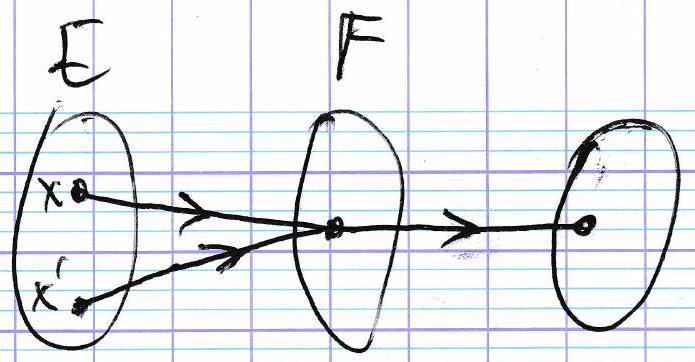

On dit que f f f E E E F F F ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( ∀ x ′ ∈ E ) ( x ≠ x ′ ⇒ f ( x ) ≠ f ( x ′ ) ) (\forall x \in E)(\forall x' \in E)(x \neq x' \Rightarrow f(x) \neq f(x')) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( ∀ x ′ ∈ E ) ( x = x ′ ⇒ f ( x ) = f ( x ′ ))

cad : ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( ∀ x ′ ∈ E ) ( f ( x ) = f ( x ′ ) ⇒ x = x ′ ) (\forall x \in E)(\forall x' \in E)(f(x) = f(x') \Rightarrow x = x') ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( ∀ x ′ ∈ E ) ( f ( x ) = f ( x ′ ) ⇒ x = x ′ )

( ∀ y ∈ F ) ( ∃ ! x ∈ E ) ( y = f ( x ) ) (\forall y \in F)(\exists! x \in E)(y = f(x)) ( ∀ y ∈ F ) ( ∃ ! x ∈ E ) ( y = f ( x ))

càd si f f f

Exemples : ¶ id E ∣ E → E x ↦ x \operatorname{id}_E \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & E \rightarrow E \\ & x \mapsto x \end{aligned} \right. id E ∣ ∣ E → E x ↦ x

f 1 : ∣ R → R x ↦ x 2 f_1: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto x^2 \end{aligned} \right. f 1 : ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ x 2

f 2 : ∣ R → R + x ↦ x 2 f_2: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+ \\ & x \mapsto x^2 \end{aligned} \right. f 2 : ∣ ∣ R → R + x ↦ x 2

f 3 : ∣ R + → R + x ↦ x 2 f_3: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R}^+ \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+ \\ & x \mapsto x^2 \end{aligned} \right. f 3 : ∣ ∣ R + → R + x ↦ x 2

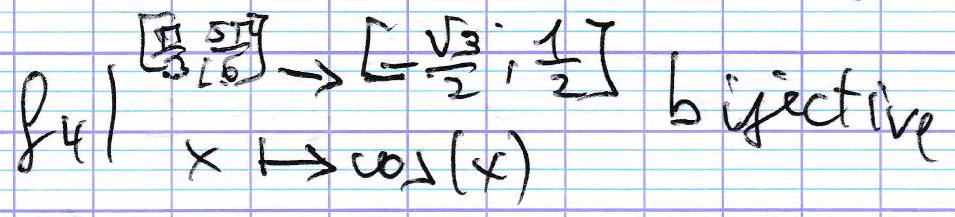

f 1 : ∣ R → R x ↦ cos ( x ) f_1: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto \cos(x) \end{aligned} \right. f 1 : ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ cos ( x )

f 2 : ∣ R → [ − 1 , 1 ] x ↦ cos ( x ) f_2: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \left[-1, 1\right] \\ & x \mapsto \cos(x) \end{aligned} \right. f 2 : ∣ ∣ R → [ − 1 , 1 ] x ↦ cos ( x )

f 3 : ∣ R → R x ↦ cos ( x ) f_3: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto \cos(x) \end{aligned} \right. f 3 : ∣ ∣ R → R x ↦ cos ( x )

f : ∣ C → C z ↦ z 2 + z f: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & \mathbb{C} \rightarrow \mathbb{C} \\ & z \mapsto z^2 + z \end{aligned} \right. f : ∣ ∣ C → C z ↦ z 2 + z

Injective : En effet, pour tout b ∈ C b \in \mathbb{C} b ∈ C z 2 + z = b z^2 + z = b z 2 + z = b

Non injective : f ( 0 ) = f ( − 1 ) f(0) = f(-1) f ( 0 ) = f ( − 1 )

f : ∣ P ( E ) → P ( E ) X ↦ X ‾ f: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & P(E) \rightarrow P(E) \\ & X \mapsto \overline{X} \end{aligned} \right. f : ∣ ∣ P ( E ) → P ( E ) X ↦ X

Soit B ∈ P ( E ) B \in P(E) B ∈ P ( E )

φ ( x ) = B ⇔ x ‾ = B ⇔ x = B ‾ ⇔ x = φ ( B ) \begin{aligned}

\varphi(x) = B & \Leftrightarrow \overline{x} = B \\

& \Leftrightarrow x = \overline{B} \\

& \Leftrightarrow x = \varphi(B)

\end{aligned} φ ( x ) = B ⇔ x = B ⇔ x = B ⇔ x = φ ( B ) φ \varphi φ φ − 1 = φ \varphi^{-1} = \varphi φ − 1 = φ

Définition :

Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F

L’application F → E y ↦ l’ant e ˊ c e ˊ dent de y par f \begin{array}{l} F \rightarrow E \\ y \mapsto \text{ l'antécédent de } y \text{ par } f \end{array} F → E y ↦ l’ant e ˊ c e ˊ dent de y par f f f f f − 1 f^{-1} f − 1

On a l’équivalence :

{ y = f ( x ) x ∈ E ⇔ { x = f − 1 ( y ) y ∈ F \left\{ \begin{array}{l} y = f(x) \\ x \in E \end{array} \right. \Leftrightarrow \left\{ \begin{array}{l} x = f^{-1}(y) \\ y \in F \end{array} \right. { y = f ( x ) x ∈ E ⇔ { x = f − 1 ( y ) y ∈ F Propriétés vis-à-vis de la composition :

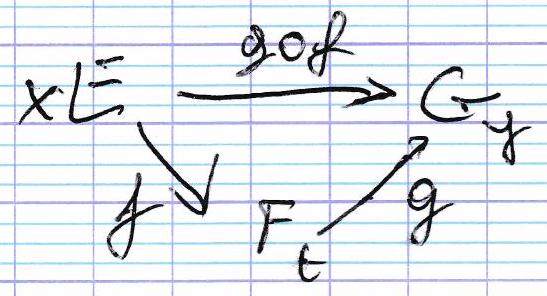

Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F g : F → G g: F \rightarrow G g : F → G

Si f f f g g g g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Si f f f g g g g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Si f f f g g g g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Preuve :

Supposons f f f g g g g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Soit x , x ′ ∈ E x, x' \in E x , x ′ ∈ E g ∘ f ( x ) = g ∘ f ( x ′ ) g \circ f(x) = g \circ f(x') g ∘ f ( x ) = g ∘ f ( x ′ )

Alors g ( f ( x ) ) = g ( f ( x ′ ) ) g(f(x)) = g(f(x')) g ( f ( x )) = g ( f ( x ′ ))

Or g g g f ( x ) = f ( x ′ ) f(x) = f(x') f ( x ) = f ( x ′ )

De nouveau, f f f x = x ′ x = x' x = x ′

Supposons f f f g g g

Soit y ∈ G y \in G y ∈ G

Par surjectivité de g g g t ∈ F t \in F t ∈ F y = g ( t ) y = g(t) y = g ( t )

Par surjectivité de f f f x ∈ E x \in E x ∈ E t = f ( x ) t = f(x) t = f ( x )

Alors y = g ( f ( x ) ) = g ∘ f ( x ) y = g(f(x)) = g \circ f(x) y = g ( f ( x )) = g ∘ f ( x )

Résulte de 1) et 2)

Propriétés :

Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F g : F → G g: F \rightarrow G g : F → G

Alors ( g ∘ f ) − 1 = f − 1 ∘ g − 1 (g \circ f)^{-1} = f^{-1} \circ g^{-1} ( g ∘ f ) − 1 = f − 1 ∘ g − 1

Preuve :

Soit y ∈ G y \in G y ∈ G x ∈ E x \in E x ∈ E

x = ( g ∘ f ) − 1 ( y ) ⇔ y = g ( f ( x ) ) ⇔ f ( x ) = g − 1 ( y ) ⇔ x = f − 1 ( g − 1 ( y ) ) \begin{aligned}

x = (g \circ f)^{-1}(y) & \Leftrightarrow y = g(f(x)) \\

& \Leftrightarrow f(x) = g^{-1}(y) \\

& \Leftrightarrow x = f^{-1}(g^{-1}(y))

\end{aligned} x = ( g ∘ f ) − 1 ( y ) ⇔ y = g ( f ( x )) ⇔ f ( x ) = g − 1 ( y ) ⇔ x = f − 1 ( g − 1 ( y )) Que peut-on dire si g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Si f f f g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f f f f

g g g

alors g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Si g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f f f f g g g

Exemple : f : R + → R + f: \mathbb{R}^+ \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+ f : R + → R + x ↦ x x \mapsto \sqrt{x} x ↦ x g : R → R + g: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+ g : R → R + x ↦ x 2 x \mapsto x^2 x ↦ x 2

g ∘ f : R + → R + g \circ f: \mathbb{R}^+ \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+ g ∘ f : R + → R + x ↦ x x \mapsto x x ↦ x g g g g ( − 1 ) = g ( 1 ) g(-1) = g(1) g ( − 1 ) = g ( 1 )

Si f f f g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f f f f

Si f f f g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f f f f

Exemple : f : R + → R 2 f: \mathbb{R}^+ \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2 f : R + → R 2 g : R → R + g: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+ g : R → R + x ↦ x 2 x \mapsto x^2 x ↦ x 2

g ∘ f : R + → R + g \circ f: \mathbb{R}^+ \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^+ g ∘ f : R + → R + x ↦ x 2 x \mapsto x^2 x ↦ x 2 f f f

Propriétés :

Soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F g : F → G g: F \rightarrow G g : F → G

Si g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f f f f

Si g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f g g g

Preuve :

Supposons g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Montrons que f f f

Soit x , x ′ ∈ E x, x' \in E x , x ′ ∈ E f ( x ) = f ( x ′ ) f(x) = f(x') f ( x ) = f ( x ′ )

Alors g ∘ f ( x ) = g ∘ f ( x ′ ) g \circ f(x) = g \circ f(x') g ∘ f ( x ) = g ∘ f ( x ′ )

Or g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f x = x ′ x = x' x = x ′

Ainsi f f f

Supposons g ∘ f g \circ f g ∘ f

Montrons que g g g

Soit y ∈ G y \in G y ∈ G

Il existe x ∈ E x \in E x ∈ E g ∘ f ( x ) = y g \circ f(x) = y g ∘ f ( x ) = y

Alors y = g ( f ( x ) ) y = g(f(x)) y = g ( f ( x )) f ( x ) f(x) f ( x ) y y y g g g

Ainsi g g g

Réciproque : soit f : E → F f: E \rightarrow F f : E → F

f f f

∃ h : F → E \exists h: F \rightarrow E ∃ h : F → E f ∘ h = id F f \circ h = \text{id}_F f ∘ h = id F h ∘ f = id E h \circ f = \text{id}_E h ∘ f = id E

Dans ce cas, h = f − 1 h = f^{-1} h = f − 1

Preuve : ¶ Montrons que la condition est nécessaire. Supposons f f f h = f − 1 h = f^{-1} h = f − 1

Montrons que la condition est suffisante. Supposons qu’il existe h : F → E h: F \rightarrow E h : F → E f ∘ h = id F f \circ h = \text{id}_F f ∘ h = id F h ∘ f = id E h \circ f = \text{id}_E h ∘ f = id E

id F \text{id}_F id F f ∘ h f \circ h f ∘ h f f f

id E \text{id}_E id E h ∘ f h \circ f h ∘ f f f f

Donc f f f

I est injective, Aind is fastbijective