Chapitres. Fonctions circulaires réciproques arcsin, arccos, arctan

Rappels:

Soit x , y x, y x , y R \mathbb{R} R f : x → y f: x \rightarrow y f : x → y ( ∀ y ∈ Y ) ( ∃ ! x ∈ X ) ( f ( x ) = y ) (\forall y \in Y)(\exists!x \in X)(f(x)=y) ( ∀ y ∈ Y ) ( ∃ ! x ∈ X ) ( f ( x ) = y )

Théorème de la bijection:

f I → R \underset{I \rightarrow \mathbb{R}}{f} I → R f I I I R \mathbb{R} R f f f f f f I I I f f f I I I J = f ( I ) J=f(I) J = f ( I ) f − 1 f^{-1} f − 1 J J J f f f

I) Fonction arcsin

Soit σ : ∣ [ − π 2 , π 2 ] → [ − 1 ; 1 ] x ↦ sin ( x ) \sigma: \left\lvert\, \begin{array}{r}{\left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right] \rightarrow[-1 ; 1]} \\ x \mapsto \sin (x)\end{array}\right. σ : ∣ ∣ [ − 2 π , 2 π ] → [ − 1 ; 1 ] x ↦ sin ( x )

La fonction σ \sigma σ [ − π 2 , π 2 ] \left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right] [ − 2 π , 2 π ] ∀ x ∈ [ − π 2 , π 2 ] , σ ′ ( x ) = cos ( x ) ⩾ 0 \forall x \in\left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right], \quad \sigma^{\prime}(x)=\cos (x) \geqslant 0 ∀ x ∈ [ − 2 π , 2 π ] , σ ′ ( x ) = cos ( x ) ⩾ 0 σ ′ ( x ) = 0 \sigma^{\prime}(x)=0 σ ′ ( x ) = 0 x = − π 2 x=-\frac{\pi}{2} x = − 2 π x = π 2 x=\frac{\pi}{2} x = 2 π σ \sigma σ σ ( − π 2 ) = − 1 \sigma\left(-\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=-1 σ ( − 2 π ) = − 1 σ ( π 2 ) = 1 \sigma\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=1 σ ( 2 π ) = 1 σ \sigma σ

Par définition, on appelle arcsinus et on note arcsin \arcsin arcsin σ − 1 \sigma^{-1} σ − 1 σ \sigma σ

On a donc l’équivalence suivante:

{ y = acsin ( x ) x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] ⇔ { x = sin ( y ) y ∈ [ − π 2 , π 2 ] \left\{\begin{array} { l }

{ y = \operatorname { a c s i n } ( x ) } \\

{ x \in [ - 1 , 1 ] }

\end{array} \Leftrightarrow \left\{\begin{array}{l}

x=\sin (y) \\

y \in\left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right]

\end{array}\right.\right. { y = acsin ( x ) x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] ⇔ { x = sin ( y ) y ∈ [ − 2 π , 2 π ] Valeurs remarquables

arcsin ( 0 ) = 0 arcsin ( ± 1 2 ) = ± π 4 arcsin ( − 1 ) = − π 2 arcsin ( ± 1 2 ) = ± π 6 arcsin ( 1 ) = π 2 \begin{array}{ll}

\arcsin (0)=0 & \arcsin \left( \pm \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right)= \pm \frac{\pi}{4} \\

\arcsin (-1)=-\frac{\pi}{2} & \arcsin \left( \pm \frac{1}{2}\right)= \pm \frac{\pi}{6} \\

\arcsin (1)=\frac{\pi}{2} &

\end{array} arcsin ( 0 ) = 0 arcsin ( − 1 ) = − 2 π arcsin ( 1 ) = 2 π arcsin ( ± 2 1 ) = ± 4 π arcsin ( ± 2 1 ) = ± 6 π La fonction arcsin est continue sur [ − 1 ; 1 ] [-1 ; 1] [ − 1 ; 1 ]

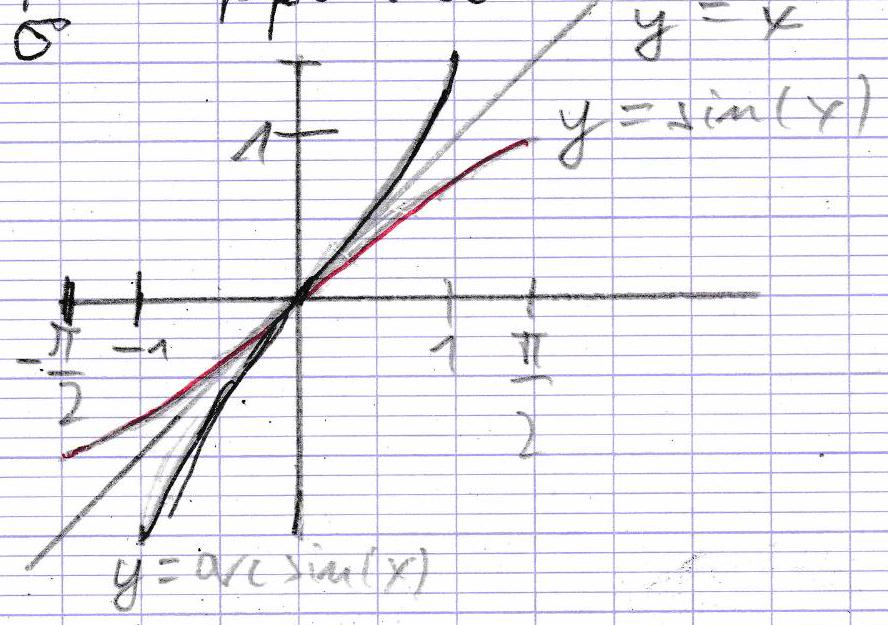

Représentation graphique ¶ La courbe représentative de arcsin \arcsin arcsin y = x y=x y = x

La fonction arcsin est impaire.

En effet, soit x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x \in [-1,1] x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] y ∈ [ − π 2 , π 2 ] y \in\left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right] y ∈ [ − 2 π , 2 π ]

y = arcsin ( − x ) ⇔ − x = sin ( y ) ⇔ x = sin ( − y ) ⇔ − y = arcsin ( x ) ⇔ y = − arcsin ( x ) \begin{aligned}

& y=\arcsin (-x) \Leftrightarrow-x=\sin (y) \\

& \Leftrightarrow x=\sin (-y) \\

& \Leftrightarrow-y=\arcsin (x) \\

& \Leftrightarrow y=-\arcsin (x)

\end{aligned} y = arcsin ( − x ) ⇔ − x = sin ( y ) ⇔ x = sin ( − y ) ⇔ − y = arcsin ( x ) ⇔ y = − arcsin ( x ) Donc arcsin ( − x ) = − arcsin ( x ) \arcsin (-x)=-\arcsin (x) arcsin ( − x ) = − arcsin ( x )

Dérivabilité de arcsin \arcsin arcsin x 0 ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x_{0} \in[-1,1] x 0 ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x \in[-1,1] x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x ≠ x 0 x \neq x_{0} x = x 0 Δ ( x ) = arcsin ( x ) − arcsin ( x 0 ) x − x 0 \Delta(x)=\frac{\arcsin (x)-\arcsin \left(x_{0}\right)}{x-x_{0}} Δ ( x ) = x − x 0 a r c s i n ( x ) − a r c s i n ( x 0 ) y 0 = arcsin ( x ) y_{0}=\arcsin (x) y 0 = arcsin ( x ) y 0 = arcsin ( x 0 ) y_{0}=\arcsin \left(x_{0}\right) y 0 = arcsin ( x 0 ) Δ ( x ) = y − y 0 sin ( y ) − sin ( y 0 ) \Delta(x)=\frac{y-y_{0}}{\sin (y)-\sin \left(y_{0}\right)} Δ ( x ) = s i n ( y ) − s i n ( y 0 ) y − y 0 arcsin \arcsin arcsin x → x 0 x \rightarrow x_{0} x → x 0 y → y 0 y \rightarrow y_{0} y → y 0

1er cas: x 0 = − 1 y 0 = − π 2 Δ ( x ) = y + π 2 sin ( y ) + 1 lim x → x 0 Δ ( x ) = lim y → − π 2 y + π 2 sin ( y ) + 1 = lim y → − π 2 1 sin ( y ) + 1 y + π 2 = + ∞ (forme 1 0 + ) \begin{aligned}

& \text{1er cas: } x_{0}=-1 \\

& y_{0}=-\frac{\pi}{2} \\

& \Delta(x)=\frac{y+\frac{\pi}{2}}{\sin (y)+1} \\

& \lim _{x \rightarrow x_{0}} \Delta(x)=\lim _{y \rightarrow-\frac{\pi}{2}} \frac{y+\frac{\pi}{2}}{\sin (y)+1}=\lim _{y \rightarrow-\frac{\pi}{2}} \frac{1}{\frac{\sin (y)+1}{y+\frac{\pi}{2}}} \\

& =+\infty \quad \text{(forme } \frac{1}{0^{+}}\text{)}

\end{aligned} 1er cas: x 0 = − 1 y 0 = − 2 π Δ ( x ) = sin ( y ) + 1 y + 2 π x → x 0 lim Δ ( x ) = y → − 2 π lim sin ( y ) + 1 y + 2 π = y → − 2 π lim y + 2 π s i n ( y ) + 1 1 = + ∞ (forme 0 + 1 ) La fonction arcsin n’est donc pas dérivable en x 0 = − 1 x_{0}=-1 x 0 = − 1 x 0 = 1 x_{0}=1 x 0 = 1 x 0 ∈ ] − 1 , 1 [ x_{0} \in]-1,1[ x 0 ∈ ] − 1 , 1 [ lim x → x 0 Δ ( x ) = lim 1 sin ( y ) − sin ( y 0 ) y − y 0 = 1 cos ( y 0 ) \lim _{x \rightarrow x_{0}} \Delta(x)=\lim \frac{1}{\frac{\sin (y)-\sin \left(y_{0}\right)}{y-y_{0}}}=\frac{1}{\cos \left(y_{0}\right)} lim x → x 0 Δ ( x ) = lim y − y 0 s i n ( y ) − s i n ( y 0 ) 1 = c o s ( y 0 ) 1

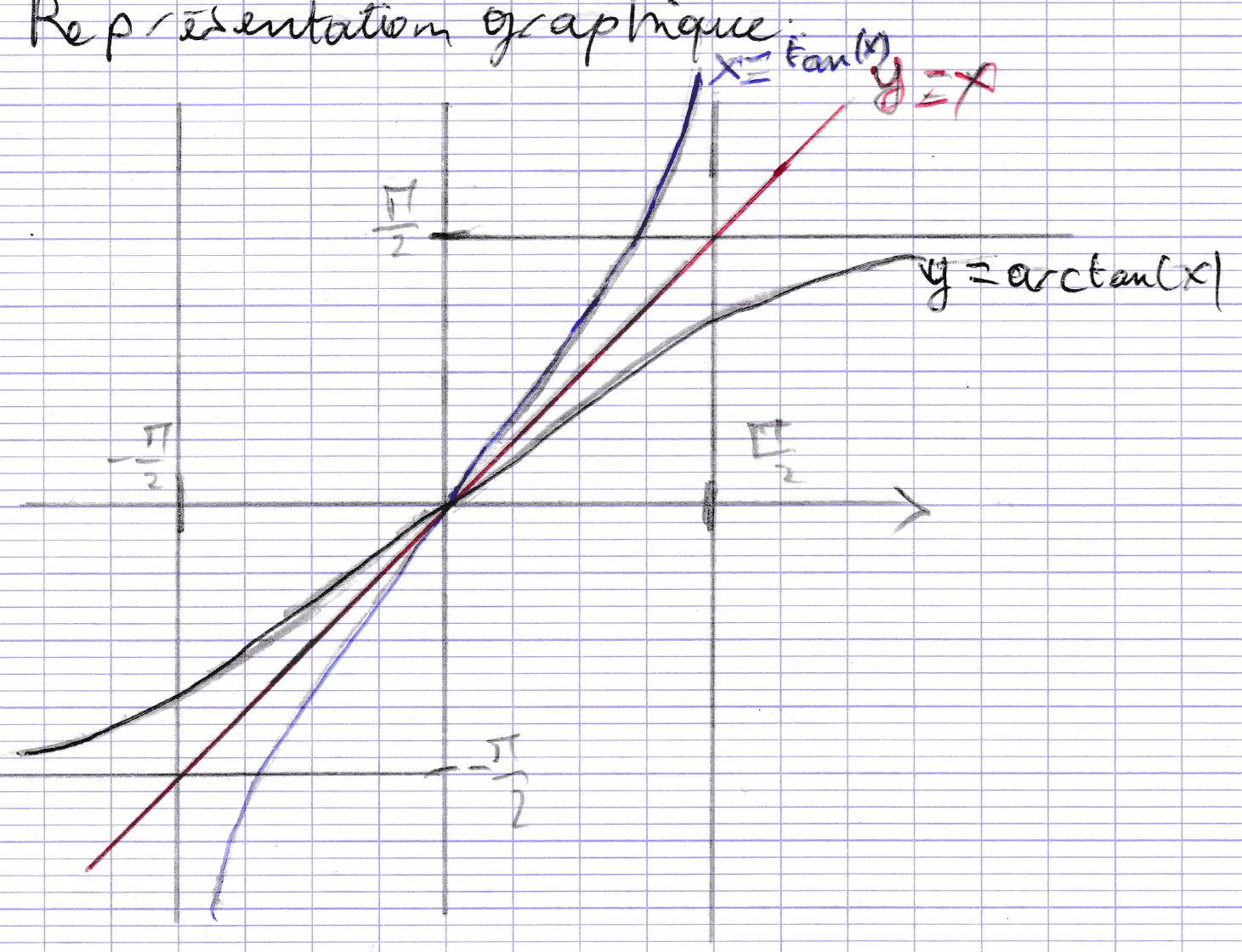

III) Fonction arctan:

La fonction ∣ ] − π 2 , π 2 [ → R x ↦ tan ( x ) \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & ]-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}[\rightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ & x \mapsto \tan (x)\end{aligned}\right. ∣ ∣ ] − 2 π , 2 π [ → R x ↦ tan ( x ) lim x → − π 2 + tan ( x ) = − ∞ \lim _{x \rightarrow -\frac{\pi}{2}^{+}} \tan (x)=-\infty lim x → − 2 π + tan ( x ) = − ∞ lim x → π 2 − tan ( x ) = + ∞ \lim _{x \rightarrow \frac{\pi}{2}^{-}} \tan (x)=+\infty lim x → 2 π − tan ( x ) = + ∞ tan \tan tan ] − π 2 , π 2 [ ]-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}[ ] − 2 π , 2 π [ R \mathbb{R} R

Par définition, on appelle arctangente et on note arctan \arctan arctan tan \tan tan

On a l’équivalence:

{ y = Arctan ( x ) x ∈ R ⇔ { x = tan ( y ) y ∈ ] − π 2 , π 2 [ \left\{\begin{array}{l}y=\operatorname{Arctan}(x) \\ x \in \mathbb{R}\end{array} \Leftrightarrow\left\{\begin{array}{l}x=\tan (y) \\ y \in ]-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}[\end{array}\right.\right. { y = Arctan ( x ) x ∈ R ⇔ { x = tan ( y ) y ∈ ] − 2 π , 2 π [ Valeurs remarquables:

Arctan ( 0 ) = 0 \operatorname{Arctan}(0)=0 Arctan ( 0 ) = 0 Arctan ( ± 1 ) = ± π 4 \operatorname{Arctan}( \pm 1)= \pm \frac{\pi}{4} Arctan ( ± 1 ) = ± 4 π Arctan ( ± 3 ) = ± π 3 \operatorname{Arctan}( \pm \sqrt{3})= \pm \frac{\pi}{3} Arctan ( ± 3 ) = ± 3 π Arctan ( + 1 3 ) = π 6 \operatorname{Arctan}\left(+\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\right)=\frac{\pi}{6} Arctan ( + 3 1 ) = 6 π

La fonction arctan \arctan arctan lim x → + ∞ arctan ( x ) = π 2 \lim _{x \rightarrow +\infty} \arctan (x)=\frac{\pi}{2} lim x → + ∞ arctan ( x ) = 2 π lim x → − ∞ arctan ( x ) = − π 2 \lim _{x \rightarrow -\infty} \arctan (x)=-\frac{\pi}{2} lim x → − ∞ arctan ( x ) = − 2 π

Elle est impaire:

En effet, soit x ∈ R x \in \mathbb{R} x ∈ R

La fonction arctan \arctan arctan x 0 x_{0} x 0 arcsin ′ ( x 0 ) = 1 cos ( y 0 ) \arcsin ^{\prime}\left(x_{0}\right)=\frac{1}{\cos \left(y_{0}\right)} arcsin ′ ( x 0 ) = c o s ( y 0 ) 1 cos 2 ( y 0 ) + sin 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 \cos ^{2}\left(y_{0}\right)+\sin ^{2}\left(y_{0}\right)=1 cos 2 ( y 0 ) + sin 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 cos 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 \cos ^{2}(y_{0})=1-x_{0}^{2} cos 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 ∣ cos ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 \mid \cos \left(y_{0}\right)=\sqrt{1-x_{0}^{2}} ∣ cos ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 y 0 ∈ ] − π 2 , π 2 [ y_{0} \in ]-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}[ y 0 ∈ ] − 2 π , 2 π [ cos ( y 0 ) > 0 \cos \left(y_{0}\right)>0 cos ( y 0 ) > 0 cos ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 \cos \left(y_{0}\right)=\sqrt{1-x_{0}^{2}} cos ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 arcsin \arcsin arcsin ] − 1 , 1 [ ]-1,1[ ] − 1 , 1 [

Mises en garde:

∀ x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] , sin ( arcsin ( x ) ) = x \forall x \in[-1,1], \sin (\arcsin (x))=x ∀ x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] , sin ( arcsin ( x )) = x

arcsin ( sin ( x ) ) = x \arcsin (\sin (x))=x arcsin ( sin ( x )) = x x ∈ [ − π 2 , π 2 ] x \in\left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right] x ∈ [ − 2 π , 2 π ]

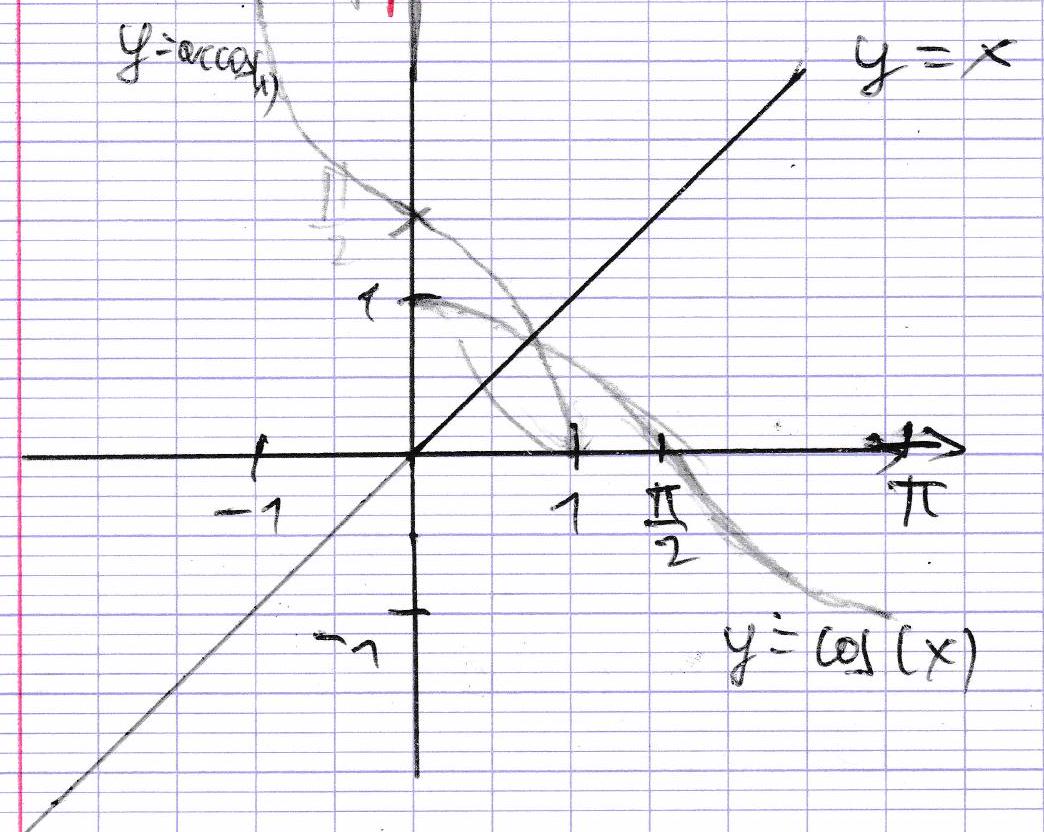

II) Fonction arccos:

Soit ζ : ∣ [ 0 , π ] → [ − 1 , 1 ] x ↦ cos ( x ) \zeta: \left\lvert\, \begin{aligned} & [0, \pi] \rightarrow[-1,1] \\ & x \mapsto \cos (x)\end{aligned}\right. ζ : ∣ ∣ [ 0 , π ] → [ − 1 , 1 ] x ↦ cos ( x ) ζ \zeta ζ ζ ( 0 ) = 1 , ζ ( π ) = − 1 \zeta(0)=1, \zeta(\pi)=-1 ζ ( 0 ) = 1 , ζ ( π ) = − 1 ζ \zeta ζ [ 0 , π ] [0, \pi] [ 0 , π ] [ − 1 , 1 ] [-1,1] [ − 1 , 1 ]

Par définition, on appelle arccosinus et on note arccos \arccos arccos ζ − 1 \zeta^{-1} ζ − 1 ζ \zeta ζ

On dispose donc de l’équivalence:

{ y = arccos ( x ) x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] ⇔ { x = cos ( y ) y ∈ [ 0 , π ] \left\{\begin{array} { l }

{ y = \operatorname { a r c c o s } ( x ) } \\

{ x \in [ - 1 , 1 ] }

\end{array} \Leftrightarrow \left\{\begin{array}{l}

x=\cos (y) \\

y \in[0, \pi]

\end{array}\right.\right. { y = arccos ( x ) x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] ⇔ { x = cos ( y ) y ∈ [ 0 , π ] La fonction arccos \arccos arccos [ − 1 , 1 ] [-1,1] [ − 1 , 1 ]

Valeurs remarquables ¶ arccos ( − 1 ) = π arccos ( 0 ) = π 2 arccos ( 3 2 ) = π 6 arccos ( 1 ) = 0 arccos ( 1 2 ) = π 3 arccos ( 2 2 ) = 3 π 4 arccos ( − 1 2 ) = 2 π 3 ⋯ \begin{array}{lll}

\arccos(-1)=\pi & \arccos (0)=\frac{\pi}{2} & \arccos \left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)=\frac{\pi}{6} \\

\arccos (1)=0 & \arccos \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)=\frac{\pi}{3} & \arccos \left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)=\frac{3 \pi}{4} \\

\arccos \left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)=\frac{2 \pi}{3} & \cdots

\end{array} arccos ( − 1 ) = π arccos ( 1 ) = 0 arccos ( − 2 1 ) = 3 2 π arccos ( 0 ) = 2 π arccos ( 2 1 ) = 3 π ⋯ arccos ( 2 3 ) = 6 π arccos ( 2 2 ) = 4 3 π Courbe représentative

Dérivabilité: ¶ Soit x 0 ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x_{0} \in[-1,1] x 0 ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x \in[-1,1] x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] x ≠ x 0 x \neq x_{0} x = x 0

Δ ( x ) = arccos ( x ) − arccos ( x 0 ) x − x 0 = y − y 0 cos ( y ) − cos ( y 0 ) \begin{aligned}

\Delta(x) & =\frac{\arccos (x)-\arccos \left(x_{0}\right)}{x-x_{0}} \\

& =\frac{y-y_{0}}{\cos (y)-\cos \left(y_{0}\right)}

\end{aligned} Δ ( x ) = x − x 0 arccos ( x ) − arccos ( x 0 ) = cos ( y ) − cos ( y 0 ) y − y 0 où y = arccos ( x ) y=\arccos (x) y = arccos ( x ) y 0 = arccos ( x 0 ) y_{0}=\arccos \left(x_{0}\right) y 0 = arccos ( x 0 ) arccos \arccos arccos x → x 0 x \rightarrow x_{0} x → x 0 y → y 0 y \rightarrow y_{0} y → y 0

lim x → x 0 Δ ( x ) = lim y → y 0 y − y 0 cos ( y ) − cos ( y 0 ) = lim y → y 0 1 cos ( y ) − cos ( y 0 ) y − y 0 1er cas: x 0 = − 1 ( y 0 = π ) lim x → x 0 Δ ( x ) = − ∞ 2e cas: x 0 = 1 ( y 0 = 0 ) lim x → x 0 Δ ( x ) = − ∞ 3e cas: x 0 ∈ ] − 1 , 1 [ lim x → x 0 Δ ( x ) = − 1 sin ( y 0 ) \begin{aligned}

& \lim _{x \rightarrow x_{0}} \Delta(x)=\lim _{y \rightarrow y_{0}} \frac{y-y_{0}}{\cos (y)-\cos \left(y_{0}\right)} \\

& =\lim _{y \rightarrow y_{0}} \frac{1}{\frac{\cos (y)-\cos \left(y_{0}\right)}{y-y_{0}}} \\

& \text{1er cas: } x_{0}=-1 \quad (y_{0}=\pi) \\

& \lim _{x \rightarrow x_{0}} \Delta(x)=-\infty \\

& \text{2e cas: } x_{0}=1 \quad (y_{0}=0) \\

& \lim _{x \rightarrow x_{0}} \Delta(x)=-\infty \\

& \text{3e cas: } x_{0} \in]-1,1[ \\

& \lim _{x \rightarrow x_{0}} \Delta(x)=-\frac{1}{\sin \left(y_{0}\right)}

\end{aligned} x → x 0 lim Δ ( x ) = y → y 0 lim cos ( y ) − cos ( y 0 ) y − y 0 = y → y 0 lim y − y 0 c o s ( y ) − c o s ( y 0 ) 1 1er cas: x 0 = − 1 ( y 0 = π ) x → x 0 lim Δ ( x ) = − ∞ 2e cas: x 0 = 1 ( y 0 = 0 ) x → x 0 lim Δ ( x ) = − ∞ 3e cas: x 0 ∈ ] − 1 , 1 [ x → x 0 lim Δ ( x ) = − sin ( y 0 ) 1 Donc: arccos ′ ( x 0 ) = − 1 sin ( y 0 ) \arccos ^{\prime}(x_{0})=-\frac{1}{\sin \left(y_{0}\right)} arccos ′ ( x 0 ) = − s i n ( y 0 ) 1

cos 2 ( y 0 ) + sin 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 \cos ^{2}\left(y_{0}\right)+\sin ^{2}\left(y_{0}\right)=1 cos 2 ( y 0 ) + sin 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 donc sin 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 \sin ^{2}(y_{0})=1-x_{0}^{2} sin 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 sin ( y 0 ) > 0 \sin \left(y_{0}\right)>0 sin ( y 0 ) > 0 sin ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 \sin \left(y_{0}\right)=\sqrt{1-x_{0}^{2}} sin ( y 0 ) = 1 − x 0 2 arccos \arccos arccos ] − 1 , 1 [ ]-1,1[ ] − 1 , 1 [

Donc

arcsin ( x ) = 1 1 − x 2 arcsin ( x ) + arccos ( x ) = 0 \begin{array}{r}

\arcsin(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^{2}}} \\

\arcsin(x)+\arccos(x)=0

\end{array} arcsin ( x ) = 1 − x 2 1 arcsin ( x ) + arccos ( x ) = 0 Donc arccos + arcsin \arccos + \arcsin arccos + arcsin ] − 1 , 1 [ ]-1,1[ ] − 1 , 1 [ arcsin \arcsin arcsin arccos \arccos arccos ] − 1 , 1 [ ]-1,1[ ] − 1 , 1 [ arcsin + arccos \arcsin + \arccos arcsin + arccos [ − 1 , 1 ] [-1,1] [ − 1 , 1 ] x = 0 x=0 x = 0 arcsin ( 0 ) + arccos ( 0 ) = 0 + π 2 \arcsin(0)+\arccos(0)=0+\frac{\pi}{2} arcsin ( 0 ) + arccos ( 0 ) = 0 + 2 π ∀ x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] \forall x \in[-1,1] ∀ x ∈ [ − 1 , 1 ] arcsin ( x ) + arccos ( x ) \arcsin(x)+\arccos(x) arcsin ( x ) + arccos ( x )

y = Arctan ( x ) ⇔ { − x = tan ( y ) y ∈ ] − π 2 π 2 [ ⇔ { x = tan ( x ) − y ∈ ] y 2 x 2 [ ⇔ − y = arctan ( x ) \begin{aligned}

y=\operatorname{Arctan}(x) & \Leftrightarrow\left\{\begin{array} { l }

{ -x = \operatorname { t a n } ( y ) } \\

{ y \in ] - \frac { \pi } { 2 } \frac { \pi } { 2 } [ }

\end{array} \Leftrightarrow \left\{\begin{array}{l}

x=\tan (x) \\

-y \in] \frac{y}{2} \frac{x}{2}[

\end{array}\right.\right. \\

& \Leftrightarrow-y=\arctan (x)

\end{aligned} y = Arctan ( x ) ⇔ { − x = tan ( y ) y ∈ ] − 2 π 2 π [ ⇔ { x = tan ( x ) − y ∈ ] 2 y 2 x [ ⇔ − y = arctan ( x ) Donc arctan ( − x ) = − arctan ( x ) \arctan (-x)=-\arctan (x) arctan ( − x ) = − arctan ( x )

Mises en garde:

∀ x ∈ R , tan ( arctan ( x ) ) = x \forall x \in \mathbb{R}, \tan (\arctan (x))=x ∀ x ∈ R , tan ( arctan ( x )) = x arctan ( tan ( x ) ) = x \arctan (\tan (x))=x arctan ( tan ( x )) = x x ∈ ] − π 2 , π 2 [ x \in] -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}[ x ∈ ] − 2 π , 2 π [

Dérivabilité: ¶ Soit x 0 ∈ R x_{0} \in \mathbb{R} x 0 ∈ R x ∈ R − { x 0 } x \in \mathbb{R}-\left\{x_{0}\right\} x ∈ R − { x 0 }

Δ ( x ) = arctan ( x ) − arctan ( x 0 ) x − x 0 \Delta(x)=\frac{\arctan (x)-\arctan \left(x_{0}\right)}{x-x_{0}} Δ ( x ) = x − x 0 arctan ( x ) − arctan ( x 0 ) On pose y = arctan ( x ) , y 0 = arctan ( x 0 ) y=\arctan (x), y_{0}=\arctan \left(x_{0}\right) y = arctan ( x ) , y 0 = arctan ( x 0 )

Δ ( x ) = y − y 0 tan ( y ) − tan ( y 0 ) = 1 tan ( y ) − tan ( y 0 ) y − y 0 \Delta(x)=\frac{y-y_{0}}{\tan (y)-\tan \left(y_{0}\right)}=\frac{1}{\frac{\tan (y)-\tan \left(y_{0}\right)}{y-y_{0}}} Δ ( x ) = tan ( y ) − tan ( y 0 ) y − y 0 = y − y 0 t a n ( y ) − t a n ( y 0 ) 1 Par continuité de Arctan, lorsqu’on a y → x 0 , y → y 0 y \rightarrow x_{0}, y \rightarrow y_{0} y → x 0 , y → y 0 lim x → x 0 A ( x ) = 1 1 + tan 2 ( y 0 ) = 1 1 + x 0 2 \lim_{x \rightarrow x_{0}} A(x) = \frac{1}{1 + \tan^{2}(y_{0})} = \frac{1}{1 + x_{0}^{2}} lim x → x 0 A ( x ) = 1 + t a n 2 ( y 0 ) 1 = 1 + x 0 2 1

La fonction Arctan est dérivable sur R \mathbb{R} R ∀ x ∈ R , arctan ′ ( x ) = 1 1 + x 2 \forall x \in \mathbb{R}, \arctan'(x) = \frac{1}{1 + x^{2}} ∀ x ∈ R , arctan ′ ( x ) = 1 + x 2 1

∫ 0 1 1 1 + x 2 d x = π 4 arctan ( x ) = ∫ 0 x 1 1 + t 2 d t \begin{aligned}

& \int_{0}^{1} \frac{1}{1 + x^{2}} \, dx = \frac{\pi}{4} \\

& \arctan(x) = \int_{0}^{x} \frac{1}{1 + t^{2}} \, dt

\end{aligned} ∫ 0 1 1 + x 2 1 d x = 4 π arctan ( x ) = ∫ 0 x 1 + t 2 1 d t Propriété ¶ Soit φ : R ∗ → R \varphi : \mathbb{R}^{*} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} φ : R ∗ → R

x ↦ arctan ( x ) + arctan ( 1 x ) x \mapsto \arctan(x) + \arctan\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) x ↦ arctan ( x ) + arctan ( x 1 ) ∀ x ∈ R ∗ , φ ′ ( x ) = 0 \forall x \in \mathbb{R}^{*}, \varphi'(x) = 0 ∀ x ∈ R ∗ , φ ′ ( x ) = 0

Donc φ \varphi φ ] − ∞ , 0 [ ]-\infty, 0[ ] − ∞ , 0 [ φ \varphi φ ] 0 , + ∞ [ ]0, +\infty[ ] 0 , + ∞ [

φ ( 1 ) = π 2 , φ ( − 1 ) = − π 2 \varphi(1) = \frac{\pi}{2}, \quad \varphi(-1) = -\frac{\pi}{2} φ ( 1 ) = 2 π , φ ( − 1 ) = − 2 π Donc ∀ x ∈ R ∗ , arctan ( x ) + arctan ( 1 x ) = ε ( x ) ⋅ π 2 \forall x \in \mathbb{R}^{*}, \arctan(x) + \arctan\left(\frac{1}{x}\right) = \varepsilon(x) \cdot \frac{\pi}{2} ∀ x ∈ R ∗ , arctan ( x ) + arctan ( x 1 ) = ε ( x ) ⋅ 2 π

où ε ( x ) \varepsilon(x) ε ( x ) x x x

lim x → 0 arcsin ( x ) x = arcsin ( 0 ) = 1 \lim_{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{\arcsin(x)}{x} = \arcsin(0) = 1 lim x → 0 x a r c s i n ( x ) = arcsin ( 0 ) = 1

lim x → 1 arcsin ( x ) 1 − x = 2 \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{\arcsin(x)}{\sqrt{1 - x}} = \sqrt{2} lim x → 1 1 − x a r c s i n ( x ) = 2

lim x → 0 arctan ( x ) x = arctan ( 0 ) = 1 \lim_{x \rightarrow 0} \frac{\arctan(x)}{x} = \arctan(0) = 1 lim x → 0 x a r c t a n ( x ) = arctan ( 0 ) = 1

Démonstration pour lim x → 1 arccos ( x ) 1 − x = 2 \lim_{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{\arccos(x)}{\sqrt{1 - x}} = \sqrt{2} lim x → 1 1 − x a r c c o s ( x ) = 2

Rappel : lim u → 0 1 − cos ( u ) u 2 = 1 2 \lim_{u \rightarrow 0} \frac{1 - \cos(u)}{u^{2}} = \frac{1}{2} lim u → 0 u 2 1 − c o s ( u ) = 2 1

Quand x → 1 x \rightarrow 1 x → 1 arccos ( x ) → 0 \arccos(x) \rightarrow 0 arccos ( x ) → 0

1 − cos ( arccos ( x ) ) arccos ( x ) → x → 1 1 2 \frac{1 - \cos(\arccos(x))}{\arccos(x)} \xrightarrow[x \rightarrow 1]{} \frac{1}{2} arccos ( x ) 1 − cos ( arccos ( x )) x → 1 2 1 Donc

1 − x arccos ( x ) → x → 1 1 2 \frac{1 - x}{\arccos(x)} \xrightarrow[x \rightarrow 1]{} \frac{1}{2} arccos ( x ) 1 − x x → 1 2 1 Donc

arccos 2 ( x ) 1 − x → x → 1 2 \frac{\arccos^{2}(x)}{1 - x} \xrightarrow[x \rightarrow 1]{} 2 1 − x arccos 2 ( x ) x → 1 2 Donc arccos ( x ) 1 − x → x → 1 2 \frac{\arccos(x)}{\sqrt{1 - x}} \xrightarrow[x \rightarrow 1]{} \sqrt{2} 1 − x a r c c o s ( x ) x → 1 2