Chapitre 7: Rudiments de logique et opérations élémentaires ensemblistes.

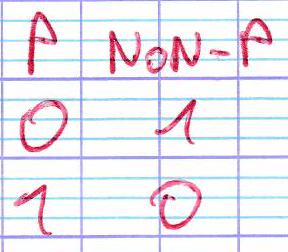

Projection, conjonction, négation.

Soient p p p q q q

p p p q q q p ET q p \text{ ET } q p ET q 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1

p p p q q q p OU q p \text{ OU } q p OU q 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1

Remarque importante : le OU en mathématiques n’est pas exclusif : il n’existe pas de cas où p p p q q q

Par exemple : un triangle isocèle possède deux côtés de même longueur ou deux angles de même mesure.

Soient p , q , r p, q, r p , q , r

p p p q q q r r r ( p ET q ) (p \text{ ET } q) ( p ET q ) ( p OU q ) (p \text{ OU } q) ( p OU q ) ( p ET r ) (p \text{ ET } r) ( p ET r ) ( q OU r ) (q \text{ OU } r) ( q OU r ) ( p ET q ) OU ( q OU r ) (p \text{ ET } q) \text{ OU } (q \text{ OU } r) ( p ET q ) OU ( q OU r ) 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

( p ET q ) ET r (p \text{ ET } q) \text{ ET } r ( p ET q ) ET r

= ( p ET r ) OU ( q ET r ) = (p \text{ ET } r) \text{ OU } (q \text{ ET } r) = ( p ET r ) OU ( q ET r ) p p p q q q r r r ( p ET q ) (p \text{ ET } q) ( p ET q ) ( p OU q ) ET ( q OU r ) (p \text{ OU } q) \text{ ET } (q \text{ OU } r) ( p OU q ) ET ( q OU r ) 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0

( p OU q ) ET r = ( p OU r ) ET ( q OU r ) (p \text{ OU } q) \text{ ET } r = (p \text{ OU } r) \text{ ET } (q \text{ OU } r) ( p OU q ) ET r = ( p OU r ) ET ( q OU r )

Lois de De Morgan :

NON ( p ET q ) = ( NON p ) OU ( NON q ) NON ( p OU q ) = ( NON p ) ET ( NON q ) \begin{aligned}

\text{NON}(p \text{ ET } q) &= (\text{NON } p) \text{ OU } (\text{NON } q) \\

\text{NON}(p \text{ OU } q) &= (\text{NON } p) \text{ ET } (\text{NON } q)

\end{aligned} NON ( p ET q ) NON ( p OU q ) = ( NON p ) OU ( NON q ) = ( NON p ) ET ( NON q ) Autres lois :

NON ( NON p ) = p \text{NON}(\text{NON } p) = p NON ( NON p ) = p

( NON p ) OU p (\text{NON } p) \text{ OU } p ( NON p ) OU p

( NON p ) ET p (\text{NON } p) \text{ ET } p ( NON p ) ET p

Implication : ¶ L’implication de q q q p p p ( NON p ) OU q (\text{NON } p) \text{ OU } q ( NON p ) OU q p p p q q q

p p p q q q p p p q q q p p p q q q p p p q q q p p p q q q p p p q q q q q q p p p p ⇒ q p \Rightarrow q p ⇒ q

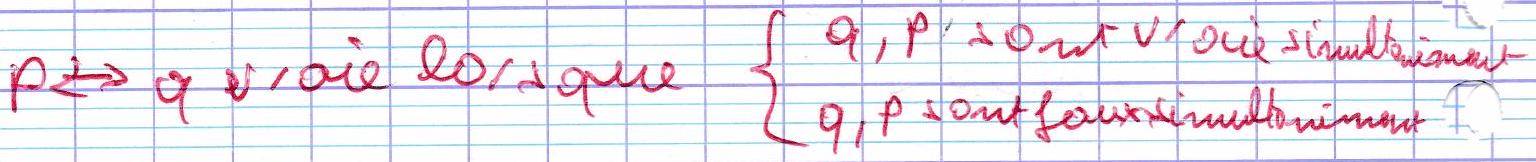

1.) ⇒ \Rightarrow ⇒ ¶ Équivalence : ¶ L’équivalence entre p p p q q q ( p ⇒ q ) ET ( q ⇒ p ) (p \Rightarrow q) \text{ ET } (q \Rightarrow p) ( p ⇒ q ) ET ( q ⇒ p ) ( NON p OU q ) ET ( NON q OU p ) (\text{NON } p \text{ OU } q) \text{ ET } (\text{NON } q \text{ OU } p) ( NON p OU q ) ET ( NON q OU p ) p ↔ q p \leftrightarrow q p ↔ q

p p p q q q p ⇒ q p \Rightarrow q p ⇒ q q ⇒ p q \Rightarrow p q ⇒ p p ↔ q p \leftrightarrow q p ↔ q 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1

Lorsque p ↔ q p \leftrightarrow q p ↔ q p ⇔ q p \Leftrightarrow q p ⇔ q p p p q q q p p p q q q r r r p p p p p p q q q

Principe de contraposition : ¶ L’implication NON p ⇒ NON q \text{NON } p \Rightarrow \text{NON } q NON p ⇒ NON q p ⇒ q p \Rightarrow q p ⇒ q

( p ⇒ q ) ⇔ ( NON q ⇒ NON p ) (p \Rightarrow q) \Leftrightarrow (\text{NON } q \Rightarrow \text{NON } p) ( p ⇒ q ) ⇔ ( NON q ⇒ NON p ) Exemple : Soit n ∈ Z n \in \mathbb{Z} n ∈ Z n 2 n^2 n 2 n n n n n n k ∈ Z k \in \mathbb{Z} k ∈ Z n = 2 k + 1 n = 2k + 1 n = 2 k + 1 n 2 = 1 + 2 ( 2 k 2 + 2 k ) n^2 = 1 + 2(2k^2 + 2k) n 2 = 1 + 2 ( 2 k 2 + 2 k ) n 2 n^2 n 2 n 2 n^2 n 2 n n n

Attention : La négation d’une implication n’est pas une implication :

NON ( p ⇒ q ) = p ET NON q \text{NON}(p \Rightarrow q) = p \text{ ET } \text{NON } q NON ( p ⇒ q ) = p ET NON q Ensembles, relations, E, C ¶ Un ensemble peut être défini par extension ou par compréhension !

W 4 = { − 1 , 1 , i , − i } (extension) U 4 = { z ∈ C ∣ z 4 = 1 } \begin{aligned}

\mathbb{W}_4 &= \{-1, 1, i, -i\} \quad \text{(extension)} \\

\mathbb{U}_4 &= \left\{ z \in \mathbb{C} \mid z^4 = 1 \right\}

\end{aligned} W 4 U 4 = { − 1 , 1 , i , − i } (extension) = { z ∈ C ∣ z 4 = 1 } Dans le cas contraire, on dit qu’il n’appartient pas à E E E x ∉ E x \notin E x ∈ / E

Un ensemble à un seul élément s’appelle un singleton.

{ 0 ⃗ } : tous les vecteurs nuls de R 2 (si 0 ⃗ = ( 0 , 0 ) ) \{\vec{0}\} : \text{ tous les vecteurs nuls de } \mathbb{R}^2 \quad \text{(si } \vec{0} = (0,0)) { 0 } : tous les vecteurs nuls de R 2 (si 0 = ( 0 , 0 )) Un ensemble de deux éléments s’appelle une paire.

E = { 0 , 1 } E = \{0, 1\} E = { 0 , 1 } Il existe un ensemble sans aucun élément, on l’appelle ensemble vide. On le note ∅ \varnothing ∅

∅ = { x ∈ R ∣ 1 + x 2 = 0 } \varnothing = \left\{ x \in \mathbb{R} \mid 1 + x^2 = 0 \right\} ∅ = { x ∈ R ∣ 1 + x 2 = 0 } Soit A , B A, B A , B A A A B B B A A A B B B

On note alors A ⊂ B A \subset B A ⊂ B N ⊂ Z ⊂ Q ⊂ R ⊂ C \mathbb{N} \subset \mathbb{Z} \subset \mathbb{Q} \subset \mathbb{R} \subset \mathbb{C} N ⊂ Z ⊂ Q ⊂ R ⊂ C A ⊂ B ⇔ ( ∀ x ) ( x ∈ A ⇒ x ∈ B ) A \subset B \Leftrightarrow (\forall x)(x \in A \Rightarrow x \in B) A ⊂ B ⇔ ( ∀ x ) ( x ∈ A ⇒ x ∈ B )

Deux ensembles A A A B B B A = B ⇔ ( A ⊂ B et B ⊂ A ) A = B \Leftrightarrow (A \subset B \text{ et } B \subset A) A = B ⇔ ( A ⊂ B et B ⊂ A )

On note ∅ ⊂ E \varnothing \subset E ∅ ⊂ E

Quantification : ¶ n’est pas un énoncé mathématique car la variable x x x

Soit E E E P ( x ) P(x) P ( x ) E E E A = { x ∈ E ∣ P ( x ) } A = \{x \in E \mid P(x)\} A = { x ∈ E ∣ P ( x )}

Cela se lit aussi : pour tout x ∈ E x \in E x ∈ E P ( x ) P(x) P ( x )

Quantificateurs et connecteurs logiques ¶ Soient P , Q P, Q P , Q E E E

( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) ET Q ( x ) ) (\forall x \in E)(P(x) \text{ ET } Q(x)) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) ET Q ( x )) ( ∀ x ∈ E , P ( x ) ) ET ( ∀ x ∈ E , Q ( x ) ) (\forall x \in E, P(x)) \text{ ET } (\forall x \in E, Q(x)) ( ∀ x ∈ E , P ( x )) ET ( ∀ x ∈ E , Q ( x ))

( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) OU Q ( x ) ) (\forall x \in E)(P(x) \text{ OU } Q(x)) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) OU Q ( x )) ( ∀ x ∈ E , P ( x ) ) OU ( ∀ x ∈ E , Q ( x ) ) (\forall x \in E, P(x)) \text{ OU } (\forall x \in E, Q(x)) ( ∀ x ∈ E , P ( x )) OU ( ∀ x ∈ E , Q ( x ))

Exemple : E = N E = \mathbb{N} E = N ( ∀ x ∈ N ) ( x est pair OU x est impair ) (\forall x \in \mathbb{N})(x \text{ est pair OU } x \text{ est impair}) ( ∀ x ∈ N ) ( x est pair OU x est impair ) ( ∀ x ∈ N , x est pair ) OU ( ∀ x ∈ N , x est impair ) (\forall x \in \mathbb{N}, x \text{ est pair}) \text{ OU } (\forall x \in \mathbb{N}, x \text{ est impair}) ( ∀ x ∈ N , x est pair ) OU ( ∀ x ∈ N , x est impair )

Cependant :

( ∀ x ∈ E , P ( x ) ) OU ( ∀ x ∈ E , Q ( x ) ) ⇒ ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) OU Q ( x ) ) \begin{gathered}

(\forall x \in E, P(x)) \text{ OU } (\forall x \in E, Q(x)) \\

\Rightarrow (\forall x \in E)(P(x) \text{ OU } Q(x))

\end{gathered} ( ∀ x ∈ E , P ( x )) OU ( ∀ x ∈ E , Q ( x )) ⇒ ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) OU Q ( x )) ( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) ET Q ( x ) ) (\exists x \in E)(P(x) \text{ ET } Q(x)) ( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) ET Q ( x )) ( ∃ x ∈ E , P ( x ) ) ET ( ∃ x ∈ E , Q ( x ) ) (\exists x \in E, P(x)) \text{ ET } (\exists x \in E, Q(x)) ( ∃ x ∈ E , P ( x )) ET ( ∃ x ∈ E , Q ( x ))

Exemple : E = N E = \mathbb{N} E = N ( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( x est pair ET x est impair ) (\exists x \in E)(x \text{ est pair ET } x \text{ est impair}) ( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( x est pair ET x est impair ) ( ∃ x ∈ E , x est pair ) ET ( ∃ x ∈ E , x est impair ) (\exists x \in E, x \text{ est pair}) \text{ ET } (\exists x \in E, x \text{ est impair}) ( ∃ x ∈ E , x est pair ) ET ( ∃ x ∈ E , x est impair ) ( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) ET Q ( x ) ) ≠ ( ∃ x ∈ E , P ( x ) ) ET ( ∃ x ∈ E , Q ( x ) ) (\exists x \in E)(P(x) \text{ ET } Q(x)) \neq (\exists x \in E, P(x)) \text{ ET } (\exists x \in E, Q(x)) ( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) ET Q ( x )) = ( ∃ x ∈ E , P ( x )) ET ( ∃ x ∈ E , Q ( x ))

( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) OU Q ( x ) ) (\exists x \in E)(P(x) \text{ OU } Q(x)) ( ∃ x ∈ E ) ( P ( x ) OU Q ( x )) ( ∃ x ∈ E , P ( x ) ) OU ( ∃ x ∈ E , Q ( x ) ) (\exists x \in E, P(x)) \text{ OU } (\exists x \in E, Q(x)) ( ∃ x ∈ E , P ( x )) OU ( ∃ x ∈ E , Q ( x ))

L’ensemble constitué par les parties de E E E E E E

Dans l’exemple précédent :

{ ∅ , { a } , { b } , { c } , { a , b } , { a , c } , { b , c } , { a , b , c } } \{\varnothing, \{a\}, \{b\}, \{c\}, \{a, b\}, \{a, c\}, \{b, c\}, \{a, b, c\}\} { ∅ , { a } , { b } , { c } , { a , b } , { a , c } , { b , c } , { a , b , c }} P ( E ) \mathcal{P}(E) P ( E ) ∀ x : X ∈ P ( E ) ⇔ X ⊂ E \forall x : X \in \mathcal{P}(E) \Leftrightarrow X \subset E ∀ x : X ∈ P ( E ) ⇔ X ⊂ E

Exemple : éléments de P ( P ( ∅ ) ) \mathcal{P}(\mathcal{P}(\varnothing)) P ( P ( ∅ ))

P ( ∅ ) = { ∅ } \mathcal{P}(\varnothing) = \{\varnothing\} P ( ∅ ) = { ∅ } Car le seul sous-ensemble de ∅ \varnothing ∅ ∅ \varnothing ∅

P ( P ( ∅ ) ) = { ∅ , { ∅ } } \mathcal{P}(\mathcal{P}(\varnothing)) = \{\varnothing, \{\varnothing\}\} P ( P ( ∅ )) = { ∅ , { ∅ }} Opérations dans M ( E ) M(E) M ( E ) ¶ Soit E E E A , B A, B A , B E E E

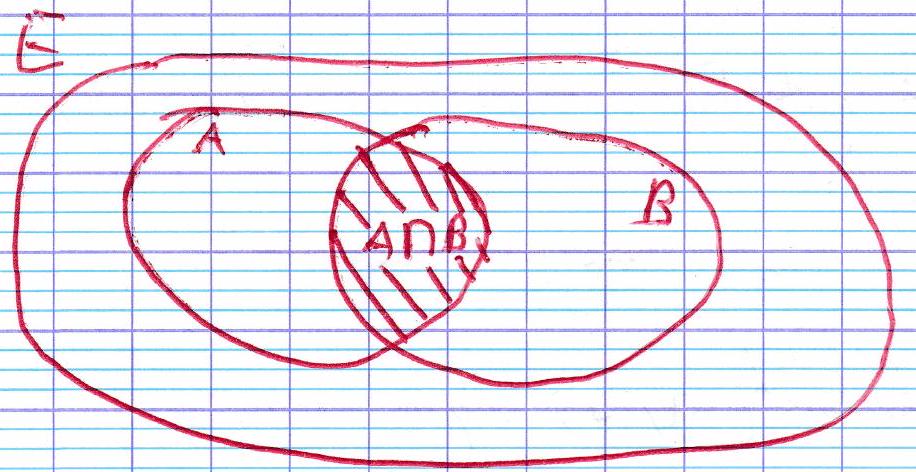

L’intersection de A A A B B B A ∩ B A \cap B A ∩ B A A A B B B

La réunion de A A A B B B A ∪ B A \cup B A ∪ B

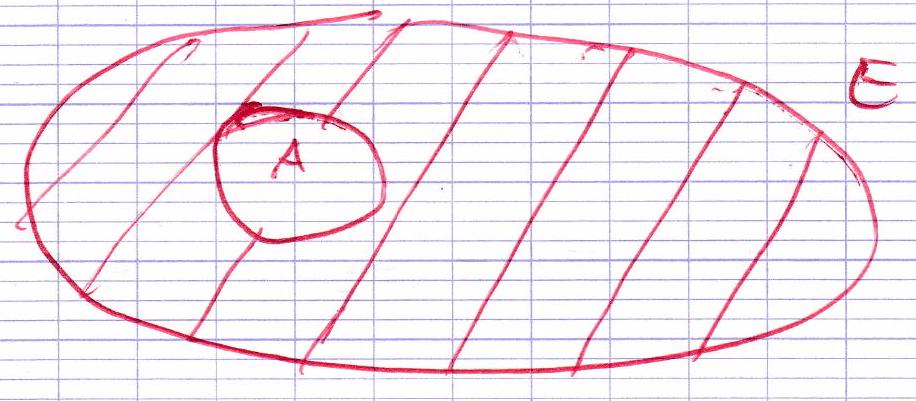

Le complémentaire de A A A E E E C E A C_E A C E A A A A

L’intersection de A A A B B B A ∩ B A \cap B A ∩ B

On note A A A

( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( x ∈ A ∩ B ⇔ x ∈ A ET x ∈ B ) (\forall x \in E)(x \in A \cap B \Leftrightarrow x \in A \text{ ET } x \in B) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( x ∈ A ∩ B ⇔ x ∈ A ET x ∈ B ) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( x ∈ A ∪ B ⇔ x ∈ A OU x ∈ B ) (\forall x \in E)(x \in A \cup B \Leftrightarrow x \in A \text{ OU } x \in B) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( x ∈ A ∪ B ⇔ x ∈ A OU x ∈ B ) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( x ∈ C E A ⇔ x ∉ A ) (\forall x \in E)(x \in C_E A \Leftrightarrow x \notin A) ( ∀ x ∈ E ) ( x ∈ C E A ⇔ x ∈ / A ) Exemple :

C E ∅ = E C_E \varnothing = E C E ∅ = E

C E E = ∅ C_E E = \varnothing C E E = ∅

∀ x ∈ P ( E ) : x ∪ ∅ = x \forall x \in \mathcal{P}(E) : x \cup \varnothing = x ∀ x ∈ P ( E ) : x ∪ ∅ = x

x ∩ ∅ = ∅ x \cap \varnothing = \varnothing x ∩ ∅ = ∅

x ∪ x = ∅ x \cup x = \varnothing x ∪ x = ∅

x ∩ x = x x \cap x = x x ∩ x = x

Propriétés : Soit A , B , C A, B, C A , B , C E E E

A ∩ B = B ∩ A A \cap B = B \cap A A ∩ B = B ∩ A

( A ∩ B ) ∩ C = A ∩ ( B ∩ C ) (A \cap B) \cap C = A \cap (B \cap C) ( A ∩ B ) ∩ C = A ∩ ( B ∩ C )

Si A ⊂ B A \subset B A ⊂ B A ∩ B = A A \cap B = A A ∩ B = A

A ∪ B = B ∪ A A \cup B = B \cup A A ∪ B = B ∪ A

( A ∪ B ) ∪ C = A ∪ ( B ∪ C ) (A \cup B) \cup C = A \cup (B \cup C) ( A ∪ B ) ∪ C = A ∪ ( B ∪ C )

Si A ⊂ B A \subset B A ⊂ B A ∪ B = B A \cup B = B A ∪ B = B

A ∩ ( B ∪ C ) = ( A ∩ B ) ∪ ( A ∩ C ) A \cap (B \cup C) = (A \cap B) \cup (A \cap C) A ∩ ( B ∪ C ) = ( A ∩ B ) ∪ ( A ∩ C )

A ∪ ( B ∩ C ) = ( A ∪ B ) ∩ ( A ∪ C ) A \cup (B \cap C) = (A \cup B) \cap (A \cup C) A ∪ ( B ∩ C ) = ( A ∪ B ) ∩ ( A ∪ C )

Lois de De Morgan : ¶ C E ( A ∩ B ) = C E A ∪ C E B C_E (A \cap B) = C_E A \cup C_E B C E ( A ∩ B ) = C E A ∪ C E B

C E ( A ∪ B ) = C E A ∩ C E B C_E (A \cup B) = C_E A \cap C_E B C E ( A ∪ B ) = C E A ∩ C E B

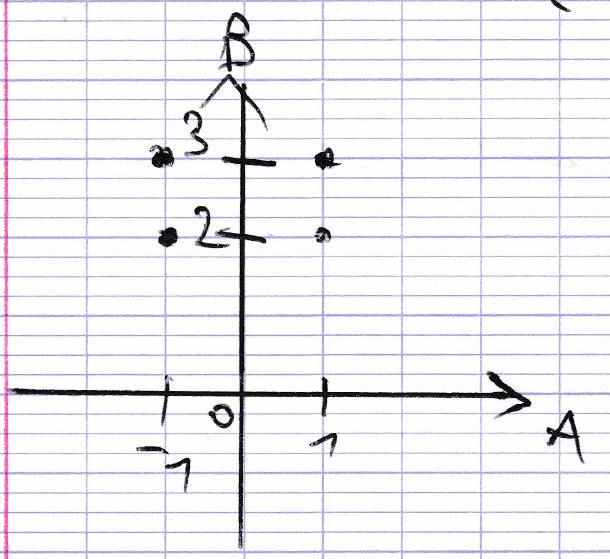

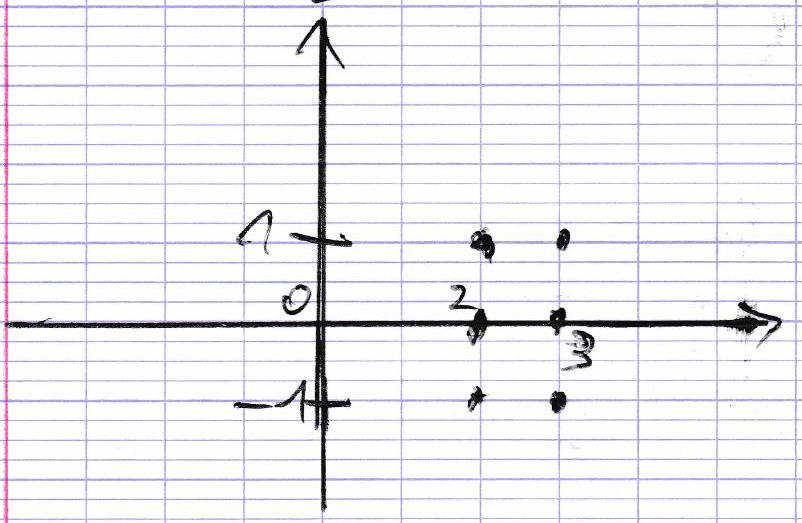

Produit cartésien : ¶ Soient A , B A, B A , B A × B A \times B A × B

A × B = { ( a , b ) : a ∈ A , b ∈ B } A \times B = \{(a, b) : a \in A, b \in B\} A × B = {( a , b ) : a ∈ A , b ∈ B } Exemple : A = { − 1 , 0 , 1 } A = \{-1, 0, 1\} A = { − 1 , 0 , 1 } B = { 2 , 3 } B = \{2, 3\} B = { 2 , 3 }

A × B = { ( − 1 , 2 ) , ( − 1 , 3 ) , ( 0 , 2 ) , ( 0 , 3 ) , ( 1 , 2 ) , ( 1 , 3 ) } A \times B = \{(-1, 2), (-1, 3), (0, 2), (0, 3), (1, 2), (1, 3)\} A × B = {( − 1 , 2 ) , ( − 1 , 3 ) , ( 0 , 2 ) , ( 0 , 3 ) , ( 1 , 2 ) , ( 1 , 3 )}

B × A = { ( 2 , − 1 ) , ( 2 , 0 ) , ( 2 , 1 ) , ( 3 , − 1 ) , ( 3 , 0 ) , ( 3 , − 4 ) B \times A = \{(2, -1), (2, 0), (2, 1), (3, -1), (3, 0), (3, -4) B × A = {( 2 , − 1 ) , ( 2 , 0 ) , ( 2 , 1 ) , ( 3 , − 1 ) , ( 3 , 0 ) , ( 3 , − 4 )

En général, A × B ≠ B × A A \times B \neq B \times A A × B = B × A

Définition : ¶ Soit A 1 , … , A n A_1, \ldots, A_n A 1 , … , A n A 1 × A 2 × … × A n = { ( x 1 , … , x n ) ∣ ∀ i ∈ [ 1 , n ] , x i ∈ A i } A_1 \times A_2 \times \ldots \times A_n = \left\{ (x_1, \ldots, x_n) \mid \forall i \in [1, n], x_i \in A_i \right\} A 1 × A 2 × … × A n = { ( x 1 , … , x n ) ∣ ∀ i ∈ [ 1 , n ] , x i ∈ A i }

( x 1 , … , x n ) (x_1, \ldots, x_n) ( x 1 , … , x n ) n n n

Si A 1 = A 2 = … = A n = A A_1 = A_2 = \ldots = A_n = A A 1 = A 2 = … = A n = A A × A × … × A ⏟ n facteurs \underbrace{A \times A \times \ldots \times A}_{n \text{ facteurs}} n facteurs A × A × … × A A n A^n A n A n A^n A n n n n

Exemple : ¶ Ex13 : Soit ( n , p ) ∈ N 2 (n, p) \in \mathbb{N}^2 ( n , p ) ∈ N 2 n p np n p n 2 − p 2 n^2 - p^2 n 2 − p 2

Ex19 : Pour tout n ∈ N n \in \mathbb{N} n ∈ N 1 + 1 2 + 1 3 ! + ⋯ + 1 n ! < e < 1 + 1 2 ! + ⋯ + 1 n ! + 1 n ! ! 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3!} + \cdots + \frac{1}{n!} < e < 1 + \frac{1}{2!} + \cdots + \frac{1}{n!} + \frac{1}{n!!} 1 + 2 1 + 3 ! 1 + ⋯ + n ! 1 < e < 1 + 2 ! 1 + ⋯ + n ! 1 + n !! 1

S n < e < S n + 1 n ! S_n < e < S_n + \frac{1}{n!} S n < e < S n + n ! 1